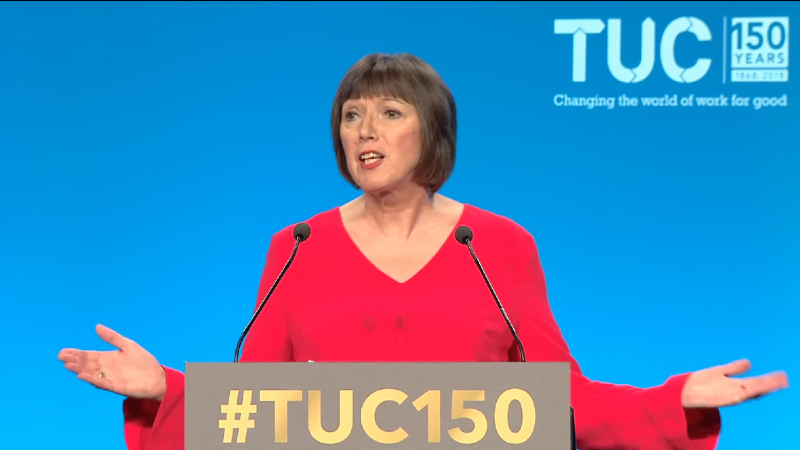

TUC general secretary Frances O'Grady speaks to Left Foot Forward about the government's plans for workers' rights, the current wave of strikes and how trade unions can help tackle the climate crisis

Frances O’Grady has been a central figure in the UK’s trade union movement for a decade. She became General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in January 2013 at the height of austerity. The aftermath of the financial crash would prove to be just one of a series of crises the trade union movement would have to respond to under O’Grady’s leadership, with Brexit and the Covid pandemic following in austerity’s wake.

Throughout this time, successive Tory led governments have been unrelenting in their attacks on working people and trade union rights. Public sector pay has been squeezed for more than decade. Unscrupulous employers have been allowed to get away with increasingly exploitative practices – from zero hours contracts to bogus self-employment. The 2016 Trade Union Act secured the UK’s place as the country with the toughest anti-union laws in Europe.

The new prime minister Liz Truss looks set to take things even further. In her leadership campaign, Truss made a series of pledges to restrict the rights and powers of organised labour, on everything from requiring minimum service requirements during strike periods to increasing the threshold of workers voting in favour of strike action for it to be legal. Reports have suggested she’s also planning to tear up key workers’ rights including protections against workers being sacked for refusing to work more than a 48-hour working week, rules on taking breaks and guarantees of four weeks’ holiday per year.

Speaking to O’Grady, she is clear about the scale of the potential attacks round the corner, describing them as a “full frontal assault on working people and our unions”, and on what she describes as a “fundamental British liberty” of the right to strike. She says, “it’s pretty clear that a Liz Truss government is coming for people’s pay packets, for their public services, for our rights at work and for our right to stand up for ourselves in terms of – when necessary – strike action.”

O’Grady goes on to make clear what she believes is behind the attacks on trade unions and workers’ rights. Describing this as a “pattern” of clamping down on the ability for workers to collectively bargain, she argues this is at the core of the proposals. She says, “I think the important thing is that this is part of a pattern of making it harder and harder for ordinary people to bargain for better pay and conditions. At its heart that is what it is about – it’s about weakening our hand at the bargaining table, and making it easier for P&O style bosses to treat workers like dirt.”

While this assessment is undeniably bleak, O’Grady is not deterred. Saying she has “great faith in the strength and ingenuity of working people”, O’Grady points to concessions won from the Cameron government in the 2016 Trade Union Act as evidence of the ability of the trade union movement to resist the forthcoming attacks. She says, “I know that the government doesn’t believe it got a 100% victory last time, because you’ll recall that we worked right across the political spectrum in both the Commons and the Lords to water down and dilute a lot of the attacks and some of them we got rid of altogether, because they didn’t bare much scrutiny. I remember vividly discussions about whether the state should be able to tell pickets what they should wear on a picket line, for example. It was bizarre.”

The latest crackdown on the ability of trade unions to effectively advocate for their members comes at a time when the biggest wave of industrial action in many years has swept across the country. High profile disputes on the railways are just the tip of the iceberg, with postal workers, dock workers and even barristers engaged in sustained strikes, and firefighters, university lecturers and nurses possibly joining them later this year.

The strikes have followed the ongoing cost of living crisis and years of wage suppression. O’Grady argues the issues of low pay, and an inability for many to make ends meet has been longstanding. She says, “This is is a problem that working people have been facing for over a decade of seeing wage freezes and real pay cuts at the same time as top pay has shot up. Dividend pay-outs have shot up. Many, many companies – contrary to the beliefs of some – did quite well during the pandemic on their profits. People aren’t asking for the moon but they want to make sure that their pay keeps pace – at least keeps pace – with inflation. And, more to the point, why on earth should working people have a shrinking share of the wealth that after all they produce?”

O’Grady goes on to say that strikes are merely a “symptom” of this ongoing economic malaise. She says, “For me, strikes are a symptom. The important issue is the cause. And the cause is that over a decade of workers losing out both in real terms and in terms of their share of wealth.” She continues, “I think people have a long fuse. But when it’s lit, it’s lit. And that’s what we’re seeing is that people are saying ‘we’ve had it up to here’. People have sacrificed. During the pandemic we saw the true value of people’s labour. Some people believe that for goodness sake, all those key workers – rail workers, bus workers, shop workers, care workers, cleaners – they would have to be rewarded given everything they did, they would have to be fairly rewarded. And instead, we’ve had breath-taking cynicism from this government and from some employers treating workers like dirt.”

The Labour Party has faced criticism from some in the trade union movement for its failure to wholeheartedly support this wave of strikes and for the leadership instructing its frontbenchers to not attend picket lines. However, O’Grady is positive about the party’s programme for workers’ rights. At the 2021 Labour Party Conference, the party’s deputy leader Angela Rayner announced Labour’s commitment to a ‘New Deal for Working People’, set to be implemented within 100 days of a Labour government.

This is what O’Grady says is important about the Labour Party’s position on workers’ rights at the moment. She says, “What’s important for me about the Labour Party is the commitment to the New Deal for Working People – a really important package of changes that would make a difference to working lives. Getting rid of those hated zero hours’ contracts. Tackling fire and rehire. Introducing fair pay agreements.” She goes on to add, “we’ve got to get behind that New Deal and bang the drum for it because – again as our poll showed- these are popular proposals, people know it’s only right that people should have a bit of dignity at work, so that would make a big difference. And of course, you know, to get that new deal, Labour has to win power.”

These aren’t the only policy positions O’Grady and the TUC are advocating for at the moment. They have also been pushing hard for a different approach to tackling rising energy prices that have played a key role in driving the cost of living crisis. O’Grady lays part of the blame for the eye-watering rises on privatisation, saying, “We’ve looked very closely at other countries and why it is that Britain is so exposed to this crisis”. She goes on to conclude that, “Part of it is because we went through that massive privatisation rip-off in the 1980s. So you look at other countries where they are majority – energy is majority or wholly owned by the state – and they’ve done a much better job of keeping prices down and investing in the greener future that we need. So there’s a lesson there. This is a pragmatic position. We need public ownership to be able to meet those big challenges ahead in terms of family finances, but also in terms of climate change.”

Our conversation concludes on that final point – how the trade union movement can play a key role in combatting the climate crisis. In contrast to some within the movement, O’Grady sees this as crucial. Saying the “just transition” is “the stuff I love”, she argues that trade unions are advocating for work that is “useful to society, to the planet, to the environment”. Acknowledging the challenges of bringing workers on board with the need to transition away from a high-carbon, fossil fuel driven economy, O’Grady says, “I don’t pretend any of this is easy. We’ve got real people in real jobs in communities that are terrified about what change can mean – ‘What will that mean for my livelihood, my skills and the firm I work for?’ And that’s why we need to really work closely together as a movement that is committed to meeting those carbon reduction targets, but also absolutely determined that working people aren’t going to pay the prices. This has to be done in a way that protects livelihoods.”

In January, O’Grady will hand over her role to Paul Nowak after a decade as general secretary of the TUC. Her time at the helm has seen the reversal of years of decline in trade union membership. She departs at a moment when workers across the country in a plethora of sectors are coming together in a revitalised movement to stand up for pay, jobs and conditions, on a scale not seen for a generation. Whatever the next few years hold for trade unions and the struggle for workers’ rights, it is beyond doubt that O’Grady leaves big shoes to fill.

Chris Jarvis is head of strategy and development at Left Foot Forward

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.