Regulation can be a force for good. But the UK's army of weak enforcers has failed to protect the public's interests, writes Professor Prem Sikka.

Brexit has provided the cloak for neoliberals to resurrect their favourite agenda – deregulation: the race-to-the-bottom to secure lower environmental, consumer, employment, welfare and other rights.

In many ways, the term ‘deregulation’ is a bit of a misnomer. It does not mean that there is no regulation as regulatory spaces do not remain empty. They are colonised by powerful interests who impose their preferred forms of private constraints to exploit the comparatively weak.

This is best countered by forms of public regulation consisting of rules and processes to give people enforceable rights through hard law (legislation passed by parliament) and various kinds of soft regulation (e.g. codes of conduct). When effectively designed and applied, regulation can be more effective and promote long-term social interests, by empowering employees, stakeholders and citizens. It’s time to change a debate that has been dominated by the right for too long.

Regulation as a positive force

Contrary to the claims of neoliberals, regulation has played a key role in democratisation of the workplace, protection of workers, health and safety, consumer rights, gender and racial equality and much more. It is regulation which gives people a decent wage, healthcare, education and pensions. Governments have also introduced rules, procedures and policies to address market failures. The regulatory state intervenes to invest in the areas of biotechnology, telecommunication, computing and aerospace, especially when private interest were not willing to invest and take long-term risks.

Public regulation has been used to prohibit undesirable practices. For example, in pursuit of profits some businesses have engaged in price fixing cartels to fleece customers. In response to public pressure, the state has been persuaded to enact legislation and create regulatory bodies to check collusion amongst suppliers. The tobacco and alcohol industries did not voluntarily restrict the sale of their products, which can cause poor health and premature death. That constraint had to be imposed by the state.

Public regulation introduces order and norms. Without it, there would not be even a minimal level of trust in the financial system – banks, insurance or pension companies – people would not be persuaded to entrust their earnings or invest their savings with them. Likewise, the transport system requires rules about levels of safety of automobiles, trains, airplanes, roads, railway tracks and air traffic controls; and the food and medical industries depend – are constrained but also enabled – by controls over contents and their safety.

The 2007-2008 banking crash showed how poor regulation, regulatory architecture and enforcement in the financial system can have serious consequences for the stability of the economy. In the absence of adequate regulation and enforcement, banks are unlikely to maintain minimal capital and may engage in excessive leverage, and pay little attention to the knock-on effects of their recklessness. After bailing-out distressed banks, the state has imposed minimum capital requirements for banks. Previously, it introduced a depositor protection scheme in addition to acting as a lender of the last resort.

The disorganised state

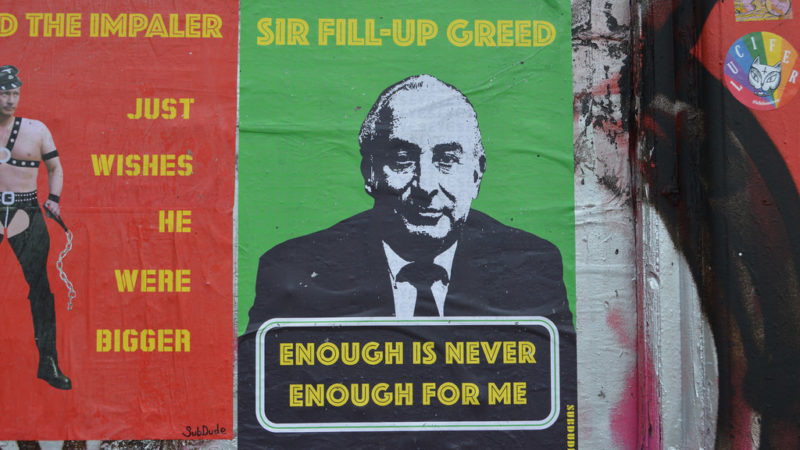

The UK has a nearly 700 overlapping regulatory bodies. There are 41 regulators for the financial sector alone and at least 14 dealing with accounting, auditing, insolvency and some aspects of corporate governance. Even then there is no central enforcer of company law. There is little coordination to deal with corporate scandals, auditing failures, looting of pension schemes, insolvency abuses, tax avoidance, money laundering and general abuse of consumers and citizens. Uncomfortable events are ignored or swept under dusty-carpets. Too many trade associations act as statutory regulators and have no independence from the very interests that they regulate. The sanctions against wrongdoers are puny and ineffective.

The poverty of regulators is exemplified by the Financial Reporting Council (FRC), a body responsible for regulating auditors. It has been dominated by the big accounting firms, the very firms that it is supposed to regulate. Inevitably, it failed to introduce robust auditing standards, promptly investigate audit failures and imposed puny sanctions. Audit failures at BHS, Carillion, banks, AssetCo, Patisserie Valerie and resultant loss of jobs, savings and pensions are a reminder of the social cost of poor and ineffective regulators.

A new model

Regulation has too often produced bloated bureaucracies that are both unaccountable to the people and ineffective. So a recent report submitted to the Labour Party puts forward a stakeholder model of regulation that is independent of government departments and reports directly to parliament, so that Ministers cannot stymie investigations or suppress critical reports in pursuit of narrow short-term political party or economic advantages.

The report calls for urgent reforms to democratise the regulatory structures so that stakeholders can direct, scrutinise and supervise regulatory bodies that have been too timid for too long.

It recommends that every regulatory body should be directed by a Supervisory Board consisting of a plurality of stakeholders. This will act as a bulwark against capture and enable stakeholders to examine delay, obfuscation and lack of effective action by the regulatory body and ultimately fire the regulator.

In the post-Brexit era, regulation needs to be reconstructed to serve the needs of the people rather than continuing to be a fig leaf for the interests of big corporations. All parties need to wake up to this.

Prem Sikka is Professor of Accounting at University of Sheffield and Emeritus Professor of Accounting at University of Essex. He is a Contributing Editor of Left Foot Forward and tweets here.

Read Prem Sikka and colleagues’ recent report on overhauling Britain’s regulatory system here.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.