Companies should have a two-tier system of corporate management, a new board of stakeholders balancing out the power of the shareholders.

All the signs are that the recent decline in the real wages of workers is likely to continue. Despite record corporate profitability and corporation tax cuts, more people are trapped at the bottom.

In 1999 only one-in-fifty employees were being paid the minimum wage, but in 2015 one-in-twenty employees (or approximately 1.5 million individuals) were on the minimum wage and more than one-in-five employees (about 6.3 million individuals) were paid less than the voluntary Living Wage.

All wealth is created by the collective effort of stakeholders, but a large and ever growing proportion of it is being appropriated by company executives.

Remuneration committees and non-executive directors (often buddies of executive directors) have failed to check fat-cattery. FTSE 100 chiefs (mostly men) still collect around 160 times the average wage in their companies.

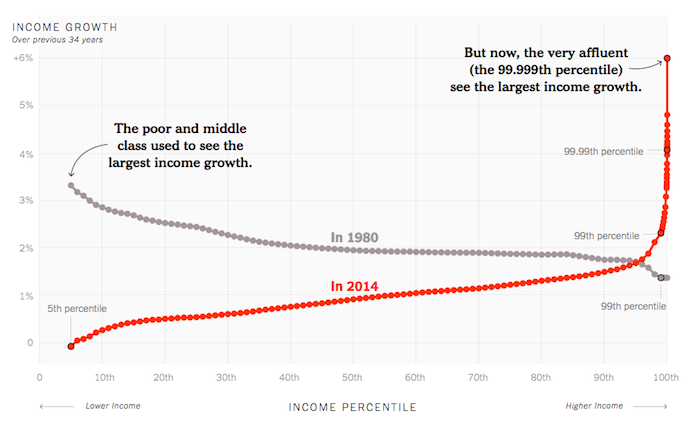

Unsurprisingly, over the last 30 years the share of income going to the top 1% has more than doubled from 6% to 14%.

The pay at the top has little to do with actual performance of companies. This is illustrated by banks who have been bailed out by taxpayers.

The finance sector has been engaged in mis-selling financial products, rigging foreign exchange rates, interest rates, money laundering, tax avoidance and tax evasion to boost profits and performance related pay.

Banks have paid large fines for malpractices but their executives still continue to collect large pay-packets.

The inequitable distribution of income has serious consequences because they affect people’s access to housing, education, transport, job mobility, pensions, healthcare, life expectancy and ability to influence political parties.

Tackling income and wealth inequality is a complex issue, especially as a large amount of wealth is inherited. It requires action on many fronts, including the way the income and wealth created by employees is shared.

The typical response of successive UK governments has been to call upon shareholders to shackle fat cattery. Numerous studies have shown that shareholders have only a short-term interest in major companies and their main priority is to secure the best returns for themselves.

So we need new mechanisms to shackle fat-cattery at the top and at the same time secure a more equitable outcome for workers. What might these be?

In short, long-term stakeholders need to be empowered to check fat-cattery and secure equitable distribution of income.

Employees and other stakeholders (e.g. savers, borrowers at banks) have a long-term interest in the wellbeing of a company but have no say on corporate governance matters currently.

The best way of empowering stakeholders is to democratise corporations. Company law should be changed and require large UK companies to have a system of two-tier boards.

Currently, almost all UK companies have a unitary (or a single) board consisting of executive directors who run companies as their private fiefdoms. This should be replaced by a two-tier system.

The first-tier should consist of an Executive Board and its members (executive directors) would remain responsible for the day-to-day running of the company.

The second tier would consist of a Stakeholder Board which would provide a strategic oversight of the Executive Board. Members of the Stakeholder Board would be directly elected by employees and other stakeholders (e.g. savers and borrowers in banks) and be accountable to them.

A major task of the Stakeholder Board would be to design and approve executive remuneration packages. The Stakeholder Board should check abuses.

As executive pay is linked to corporate earnings, executives have incentives to boost profits and trigger bonuses by sacrificing investment in the company’s future.

For example, executives boost profits in this way by deferring investment in assets, research & development, repairs and maintenance; imposing wage freezes and tax avoidance.

To check this, the Stakeholder Board, who have a long-term interest in the company’s success, should be put in charge of all the accounting and performance measurement decisions.

In designing and fixing executive remuneration packages, the Stakeholder Board should be required to demonstrate that it has given due regard to the interests of employees, and corporate investment and capital needs.

No doubt, the above modest proposal for democracy would be opposed by executives who have got used to playing their selfish games.

But emancipatory change often had to be imposed in the teeth of opposition, as demonstrated by the national minimum wage laws, and the same will be necessary again.

Prem Sikka is Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of Essex. He tweets here.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.

One Response to “Only corporate democratisation can stop the growing polarisation of pay in UK”

Michael

As Lenin said, “if in doubt, copy the Germans.”