Labour doesn't have to be in government to kick-start a green transformation.

When Labour’s Green Industrial Revolution was launched in Scarborough last summer, a new kind of politics was unveiled.

The Green New Deal promises a strategy which addresses both the climate emergency and the UK crisis of poverty and regional inequality. Within it, too, are first steps towards upskilling the workforce and creating high-quality employment. These principles are now widely accepted and will underpin the party’s economic policy, whoever becomes Labour’s next leader.

Understandably, after years of damaging neglect by the Tories, the plan focuses on ‘stuff’ – big solid infrastructure – aimed at kick-starting economic growth in left-behind regions and communities. Improved transport links, cheap sustainable energy, high-spec broadband, and regional investment banks provide a framework for business and society to flourish.

It’s ambitious. But here’s a proposal to make the picture bigger still, based on a model from history. The first industrial revolution (in full swing by the late-eighteenth century) went on to change the world, and was driven by quite ordinary people in small towns and villages. In northern England, the cutting-edge industry of the age was textile engineering, conceiving and making new kinds of machines. For this, community provided the essential dynamic.

Those achievements point to some universal truths which might boost the prospects of modern-day communities. The key in the eighteenth century was inclusivity, recognising and then harnessing local skills and ideas. Creativity and innovative thinking were central to the transformation.

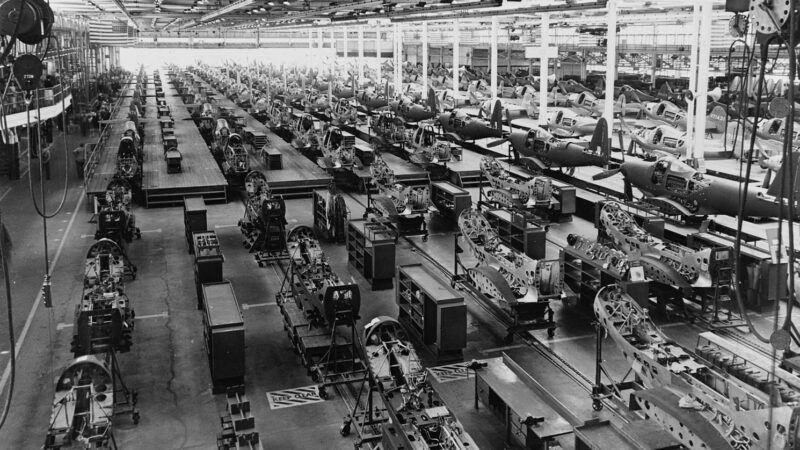

‘Industrial revolution’ conjures up visions of filthy factories, overcrowded towns, and terrible exploitation. We now know that it triggered disastrous damage to the planet, to people’s health and well-being, and to social and economic relationships. But its origins held much promise: it was born out of grassroots ingenuity.

The way that we work in twenty-first century Britain has a surprising amount in common with the world of our eighteenth-century ancestors. Towns and villages ran on a gig economy, an eclectic and changing mix of self-employment, paid work, subcontract and one-off jobs, some at home, some in a workplace. Most people lived with great financial insecurity. Small firms, employing just a few people quite flexibly, were the key building block of local economic development.

How exactly did the transformation happen? Industrialization largely began where there had been recent investment in infrastructure. The Green Industrial Revolution proposes improved railways, broadband and cheap energy; their equivalent was canals (moving coal and other commodities) and regional newspapers. Local merchants’ private banks acted as intermediaries with private investors, and new forms of security protected lending.

Communities were meshed, so individual skills and qualities (good or not so) were well known, and industry’s changing needs well understood. The crossover between industries, and through supply chains and subcontractors, broadened the available pool of expertise, ideas and resources. Very many important breakthroughs in technology and industrial systems were generated and funded locally. It was a neat communal effort to address and solve specific problems.

We can learn from this. If that is how dramatic and positive change was triggered 250 years ago, it is possible now. Alongside low-carbon initiatives, this approach can enrich and accelerate sustainable regeneration. It demands ‘soft’ as well as ‘hard’ supportive infrastructures, re-creating environments that encourage people and small business to think innovatively. It starts with a focus on clusters of industries which, as they develop and succeed, can reinforce each other; and forums where creativity (meaning all kinds of innovation, ideas and skills) can flourish.

And there are more potential gains. The ONS now measures personal alongside economic wellbeing. While regeneration might save a community’s high street, building outlets to share ideas and join in rebuilding a local economy can rescue community relationships, trust, and sanity.

With Labour out of power for years to come, many of us feel utter frustration. How can a green industrial package now be delivered? We continue the urgent priority of campaigning to raise general awareness of climate change. The new government, though, while symbolically reclaiming a handful of northern former industrial sites, has no plan.

What we do have is Labour councils and regional mayors. For them, sparking the people-powered element of an industrial revolution could be very productive. Right now, Britain needs all the imaginative thinking it can find.

Dr Gill Cookson is an economic historian who writes about the industrial revolution in northern England, 1750-1850. She is Chair of Scarborough and Whitby CLP.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.

3 Responses to “What the Industrial Revolution can teach us about a Green New Deal”

What the Industrial Revolution can teach us about a Green New Deal - Politics Highlight - News from the Left and Right

[…] 17 January 2020Politics Highlight Labour doesn’t have to be in government to kick-start a green transformation. Author: Gill Cookson | Source […]

Rural Britain needs a New Deal | Left Foot Forward

[…] See also: What the Industrial Revolution can teach us about a Green New Deal […]

Rural Britain needs a New Deal – LeftInsider

[…] See also: What the Industrial Revolution can teach us about a Green New Deal […]