Tom Pashby reviews an upcoming book on the Labour party and asks: 'Is Labour finally becoming a socialist party - albeit one with centrists in it?'

Founded by socialists, but never a socialist party – it is a view which has been said of the Labour party for many decades. But does it hold true?

Simon Hannah’s timely A Party With Socialists In It takes a sweeping look at the Labour left from 1893 through to 2017. As a notable sign of the times, the current serving Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell MP – himself a leading light of the Left in Labour, opens his foreword by repeating the central premise. For a socialist at the top of the party, it is an enlightening take.

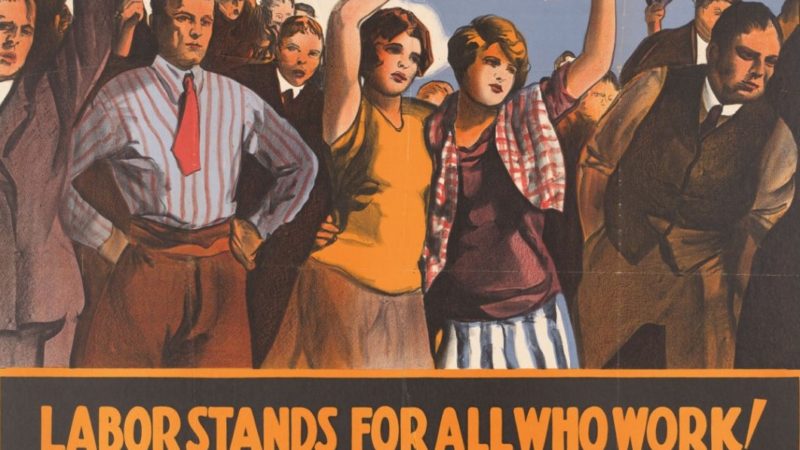

Hannah takes the reader on a journey covering the effective entry of the unions into the parliamentary system, the formation and maturation of the Independent Labour Party, through to the movement’s response to the suffragettes, the Great Wars, the second Iraq war and the global financial crisis.

Throughout the book, he examines the working class struggle against the worst of capitalism. But he also compares that to the compromises the union leaders and Labour MPs have always been willing to make in order to secure their relationship with arteries of the state and electoral success. It’s a reminder that Labour is a party of class dialogue.

Meanwhile, the external political climate – both domestically and internationally – has changed radically many times over during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We’ve seen the full roll-out of powered industry, the rise and fall of Stalinism and Nazism, two wars which engulfed the globe and the advent of the information age.

The passage of time has brought a wave of technological advances, and an expansion and concentration of wealth. Former Tory Defence Secretary Michael Portillo on Andrew Neil’s This Week recently pointed to ‘people wearing shoes’ as a sign of the success of capitalism over communism. Of course, this doesn’t mean poverty has been eliminated.

The context from Labour’s conception to now is dramatically different. But there are parallels: today we have millions in work but still in poverty. We have thousands dependent on food banks. The character and perceptions of class forces have changed significantly – but class has not disappeared.

All parties involved in mainstream politics, particularly those with parliamentary representation, face internal oppositional forces, all held in tension. Witness the decision by David Cameron to hold a non-binding referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, Labour’s tensions over Brexit, and indeed Corbyn’s election itself. For Labour, this has meant balancing the dreams of the working class, their union leaders, radical campaigners and Fabians elected in Parliament.

One key tension – relevant in the centenary of women winning the right to vote – was on female suffrage itself. While some did get behind the movement and supported it in their work as opposition MPs, there was a flinch in the labour movement with people worried that votes for (middle-class) women would break up families and lead to social anarchy. Many Labour supporters hesitated in supporting the suffragettes for fear it might mean Labour men losing their seats in Parliament.

But with an increasingly integrationist – and in places, outright neoliberal – approach to national politics from the middle of the 20th Century, support for old trade union values were slipping away in the Parliamentary Labour Party.

As we know, towards the end of the Blair/Brown project, socialism and otherwise distinctly left politics had been forced outside of mainstream, establishment Labour thought.

Hannah notes that a pivotal point in this was when Harriet Harman instructed her front bench to abstain from the Welfare Bill – the Tories’ key attack on support for the some of the most vulnerable. We may look back on that point as a crucial moment in Labour’s story – and its subsequent shift to the left.

The Labour party has been, from its birth, a party of contradictions and internal division. With a unilateralist, vegetarian, self-proclaimed socialist Jeremy Corbyn now leading the party in 2018 – having faced multiple backbench rebellions by the Labour right – many are hoping this is a new and long-term shift in Labour’s history.

Perhaps Labour’s motto is destined to become: ‘A Socialist Party with Centrists in it’…

‘A Party With Socialists In It: A History of the Labour Left’ by Simon Hannah is out on the 15th February, and is published by Pluto Press.

Tom Pashby is a reviewer for Left Foot Forward, and tweets here.

5 Responses to “History shows that Labour has always been a party of compromise”

Dave Roberts

What is being ignored here, as always, is the average Labour voter. I was born two years after the first postwar Labour government was elected and my extended east London family was solidly Labour. They were also very socially conservative Irish Catholics who would have nothing to do with the more extreme elements of the party either then or now. This article, and presumably the book as well, raises more questions than it solves, the first being what is socialism. Until someone can come up with a definition of that then this latest effort is just more trees chopped down and pulped.

Terry McCarthy

from 1918 onwards there has always been a struggle between social Democrats and socialists in the Labour party the Social Democrats not only wrote clause 4 they accepted it up until Ramsay MacDonald split the party Labour leaders George Lansbury and Clement Attlee accepted clause 4 Gaitskell did-not Wilson did Callaghan didn’t Neil Kinnock did and then he didn’t John Smith did Tony Blair didn’t, luckily now is not up to the leadership but the membership whether they will bring back clause 4.The aims and objects as outlined by the founders of the party are clearly socialist, unfortunately we can’t seem to stop entryism from the right

Jimmy glesga

Dave Roberts, I would agree with you that Catholicism is more important to Catholic socialists than socialism. The soul is more important than social justice.

Das

The amendment written into the clause 4 withdrawal during Blair has not been implemented.

Time to reinstall it.

Tony

Re Clause 4: A clear distinction needs to be made between retaining it in Labour’s constitution and supporting the implementation of it. They are two completely different things.

Tony Blair ditched clause 4 from Labour’s constitution. However, in his autobiography, Jack Straw claims that he did much of the groundwork before Blair became leader.

He tried unsuccessfully to persuade John Smith who did not think it worth the effort.

Straw also claimed that clause 4 meant nationalisation whereas it actually meant common ownership which is not really the same thing.

I hope that priority will be given to achieving a clear anti-nuclear stance for Labour at the next election so that we can help move towards a world without the threat of nuclear annihilation.