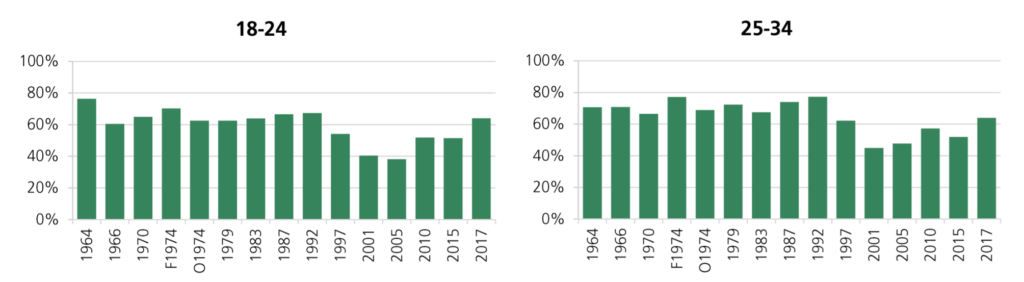

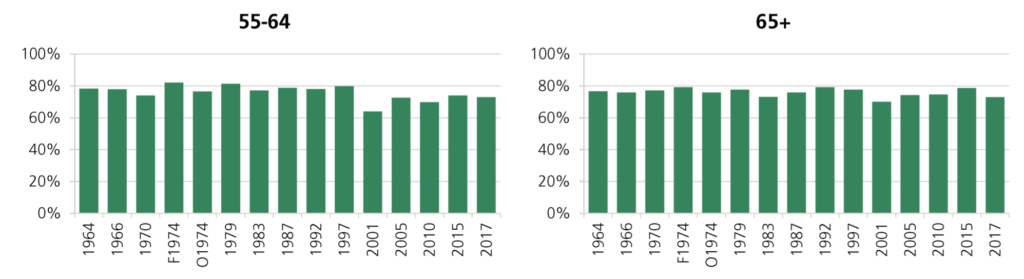

New figures reveal turnout among 18-24 year olds rose above 60% this election – for the first time since 1992. This is a game-changer.

Britain’s most trusted election study has just rebuffed the doubters: young people came out in their biggest numbers for decades this general election.

For months before the election we heard time and again that the left’s plan to mobilise young people was doomed. That young people could not swing the result. We even heard this from young people – trapped in the idea that we would play no role. It doesn’t get much bleaker than this line:

“Our vote will have no impact in the upcoming general election.”

It’s nice to be proven wrong, with the release of the British Election Study yesterday – the most in-depth analysis of General Elections in the UK. It’s shedding a lot of light on June’s result.

There were a lot of figures thrown around after polling day. An Ipsos MORI poll put 18-24 turnout at 54%, while an NME exit poll said 53%. Many on the left pitched the figure as 72% – an evidence free claim at the time, debunked by Channel 4 fact-checkers. But now we have the sturdiest estimates yet – and they suggest a relative ‘youthquake’.

New figures revealed by the House of Commons Library show that turnout among that group rose above 60% this election – for the first time since 1992. It goes without saying that it’s a game-changer.

Not only that – turnout actually fell among older voters (something backed by research here), uninspired by Theresa May’s vision of…well whatever she was meant to have a vision of.

The surge in youth turnout was far greater than the overall two percentage point rise – suggesting it was young people who deprived the Conservatives of their majority. Professor John Curtice noted the swing to Labour was greater in seats with a higher population of 18 to 24-year-olds.

Given the vagaries of Britain’s voting system, it wouldn’t take a much greater push among young people to shift the result next time. In Richmond Park, Tory Zac Goldsmith won back his seat from the Lib Dem’s Sarah Olney with a majority of 45. In Southampton Itchen, Conservative Royston Smith took the seat with a majority of just 31.

Of course it can go either way – there are many Labour seats with tiny majorities. Six of the ten slimmest majority wins went to Labour in fact. And the race was even closer in Scotland. The SNP held onto the Fife North East seat by just two votes – 0.005% of the vote – after three recounts.

Next time – and it may come sooner than we think – we’ll be without the cynicism that spoke so surely of a youth apathy. Young people have tasted power at the ballot box, and that feeling’s not going away anytime soon.

Josiah Mortimer is Editor of Left Foot Forward. Follow him on Twitter.

One Response to “Revealed: How the General Election saw a surge in the youth vote”

Alex Folkes

You are right to point out that the turnout among 18-24 year olds was higher than has been seen in a UK general election for at least 25 years. And those voters broke overwhelmingly for Labour. In part because they always do, but also because of the Corbyn factor.

But there is an additional issue too. It wasn’t just turnout, but also the number of younger voters on the register that was higher than it might otherwise have been. Despite the switch to individual registration which had been expected to affected younger electors more than other groups, a very high percentage of those registering late (albeit that only 30% were actually new) were young voters and that only added to those who had joined the register over the previous 2 months. They registered and they voted.

Why?

I think that you have to look back for the answer. The EU referendum campaign saw an even higher turnout rate among the youngest eligible demographic. This was an issue that mattered hugely to them and the vast majority, three or four to one, favoured remain. The main Stronger In campaign was pretty dire when it came to engaging young electors. They relied on facts and experts rather than seeking to create an emotional bond with the issue. Their attempts at direct engagement were laughed at. From the #Votin video (https://youtu.be/XE8y4N_-ksw) to their decision to nominate two 60 year old white men for the supposed ‘youth debate’, they failed to hit the mark. But there were other campaign groups which did things differently, including the campaign I worked on – We Are Europe. We concentrated our efforts on creating that emotional bond and on those aspects of our relationship with Europe that really matter to young people – the freedom to travel and study abroad, the protection for the environment and social rights. And we spent a large proportion of our campaign budget simply trying to get people registered and voting. We weren’t alone – the excellent 5 Seconds series produced by the ad agency Adam & Eve did more than most to get across the ‘voting is easy and it matters’ message.

Of course, there were other factors too. But these campaigns helped to motivate massive chunks of the younger population who really didn’t give a damn about politics and persuade them that their vote counted.

It didn’t tip the balance in favour of Remain, but the legacy was an only slightly diminished cohort of energised electors who were ready to play their part in this year’s election. And they overwhelmingly backed Corbyn and Labour.

What might be annoying to me (a Lib Dem) and those I worked with on We Are Europe (mainly non-party people but with some prominent Greens) is that Corbyn and Labour benefited from our efforts despite being so lukewarm on the referendum themselves. But that is politics for you.

But the reckoning will come. As Labour’s election co-ordinator Andrew Gwynne has said, holding on to that new support will be the key. Will younger voters stick with the party if it doesn’t do all it can to remain in the EU (or at least avoid hard Brexit?) That is an almost impossible line for Labour to hold. Do they alienate older people in the north or younger people across the country? And will younger voters view Corbyn differently than they did Nick Clegg over the latest u-turn on tuition fees?

The EU referendum and campaigns like We Are Europe got Labour into a position where they could win, but can they actually do so or will they now go backwards?