We have savage reductions in the right to protest; we have deeply concerning directions of travel for democracy and freedom of speech.

On Saturday, I was speaking at a protest against the proposed new coal mine in Whitehaven in Cumbria, which is opposed by, among others of my fellow peers who are far from radicals, Lord Stern of Brentford and Lord Turner.

They have made similar points to those I was making about the messages we are sending to the international community, how it is weakening attempts to end, as the International Energy Agency says we must, new fossil fuel development.

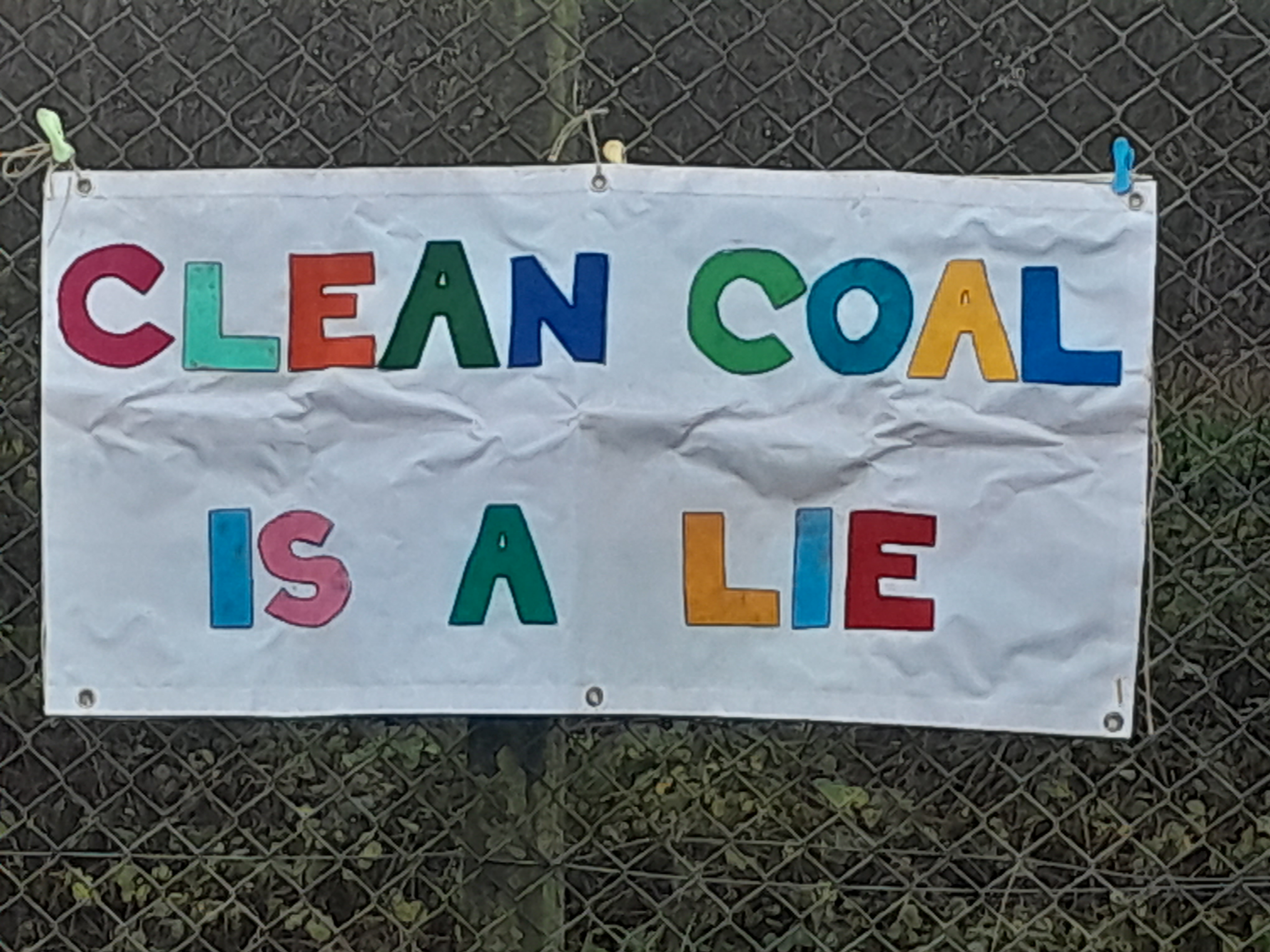

The protest slogan was “No Time for a Coal Mine”; the atmosphere, of cheerful determination, reminding me of the many similar anti-fracking events at which I have spoken.

At that protest, there were 100 or so supporters, and the four of us who were speaking had all advertised this fact on social media beforehand. For nearly all the two and a half hours we were there, flying above us was what I am told was a police drone.

The event was widely advertised, and entirely peaceful with no plans for direct action. Yet at least six police officers, one of whom filmed my contribution and all the other contributions, were in attendance. That is the experience of people peacefully protesting within the UK.

There was another story at the weekend that 15 government departments are monitoring the social media activity of potential critics and compiling files to block them from speaking at public events. This is the experience that people have of the UK state today. We have savage reductions in the right to protest; we have deeply concerning directions of travel for democracy and freedom of speech.

This was the context in which the House of Lords was yesterday debating the Investigatory Powers (Amendment) Bill, which started with us and will then go down to the Commons.

This is further strengthening the Investigatory Powers Act, which, when it was brought in in 2016, was known universally as the snoopers’ charter. Liberty described it as “the most intrusive mass surveillance regime of any democratic country”.

Since then, a number of court cases brought by Liberty have brought in some restrictions in terms of the operations of the Act, which I very much applaud, but the Act was also subject to a petition from 212,000 people to speak out against the snoopers’ charter.

Yet the speed at which we are operating now makes it very difficult to get such level of public engagement as we saw in 2016.

We are talking about a further erosion of privacy. In essence, the Bill lays the foundation for the Government to use rapidly developing artificial intelligence—so-called; I prefer to call it big data wrangling—in mass surveillance. Not only does this have huge ethical ramifications, but its adoption in surveillance would be extremely irresponsible, given that we do not know how these technologies are going to evolve in future.

The Bill gives the Government unprecedented powers to monitor and target the entire British population and lays the foundation for use of artificial intelligence in surveillance. This is indiscriminate surveillance. Anyone can be monitored, regardless of whether they are a suspect.

In addition, the potential use of artificial intelligence as part of this Bill means that the Government could in theory identify everyone who is behind every single anonymous social media account, meaning that nobody would have anonymity online. Many people express concerns about anonymity and the behaviour of anonymous accounts online. But, for example, the UK has welcomed many exiles from Hong Kong who have sought refuge in the UK, but they remain deeply fearful about the very long arm of the Chinese state. Similarly, we have seen that many Russians have had good cause for concern about the long arm of the Russian state, which, despite the best efforts of our intelligence service, has proved itself capable of reaching within our borders.

Anonymity is crucial to some people’s safety in the world. Lest we think of this as being just about states regarded as hostile by the UK Government, let us all remember the fate of Jamal Khashoggi and the actions of our “friend and ally” Saudi Arabia in his horrific death.

The widespread use of surveillance means that this Bill would push the UK further away from what are considered democratic norms. The UK likes to present itself as a leader, a model of democracy, speaking up for democracy in international contexts. We must not be a leader in allowing further steps towards autocracy.

These technologies have often been used in discriminatory ways. We know that the police, certainly, have unfairly singled out people based on their identity, and that has had dangerous, damaging consequences, both in relation to the treatment of individuals and in relation to communities’ views of the police and our security services. If artificial intelligence is added into this mix, we know that there are built-in biases in the way in which the databases have been developed, and that is a real issue.

We also know that the police and security services in the UK have made disproportionate efforts to monitor politically active individuals, trade unionists and whistleblowers. Providing the police and the security services with greater surveillance capacities means that people who are acting democratically in our society could be—in fact, will be—subjected to further unwarranted surveillance.

The complete debate can be found here.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.