History suggests Labour should be looking at over 500 gains

Looking just at opinion polls, you’d expect Labour under Keir Starmer to be rubbing their hands with glee heading into next week’s local elections. But after less-than-stellar performances in 2021 and 2022, Starmer is struggling to shake off fears of another poor result. Expectations are high: his party has a big lead, the government is widely unpopular, and Labour has performed consistently poorly in local elections since 2014 (meaning the bar for success is low). Both the current political context and history, though, suggests that Labour should be anticipating an exceptional result next week – not just a mediocre one.

This year’s local contests are England’s biggest set of local elections since 2019 (Scotland and Wales elected all their councils last year). More than 8,000 seats on 230 councils will be chosen, as well as four elected Mayors. Most of these seats were last contested in May 2019, amidst uncertainty over the future of Brexit. Labour was polling just 28%, the PM and opposition leader were both unpopular, and 49% of voters were backing small parties. This was reflected in the results: the Tories lost over 1,000 seats, but Labour went backwards too, and the big winners were small parties and independents.

Flash forward to four years later, and all those factors have changed. Labour enjoys a healthy poll lead of 16pts and a 45% poll share, both major party leaders have respectable approval ratings and two-party politics has strongly reasserted itself. Facing a more conventional political context, along with sky-high inflation and a governing party that has had three different leaders in the space of ten months, Labour is in much better shape than in May 2019.

Objectively speaking, these sorts of circumstances should lead to big gains for Labour. Looking at the past three decades of local elections (excluding contests held alongside general elections), on average the opposition made gains representing 6.5% of seats up for election – the equivalent of Labour gaining 500 council seats in May 2023. If you only look at occasions where the opposition led by double-digits (as they do now), then we can raise our expectations further – this data suggests Labour should expect gains of around 800 seats (+10%) next week.

This latter result would make Labour the largest party in local government for the first time since 2002, so it would be quite a stunning result. Yet it is also what an opposition leader would expect in these sorts of circumstances. When Miliband led by double-digits in 2012, he made gains representing 22% of total seats; Blair gained 1,600 seats (15% of seats) when leading in polls by a big margin in 1995.

In addition to this, the Conservatives are unpopular to an extent that reverberates far beyond just headline voting intention. 72% think the party is managing inflation badly, Labour is the preferred party to manage the economy, a majority of voters think the Tories are incompetent and Sunak continues to trail Starmer in ‘Best PM’ polling. This may change before the next general election, but as of right now the Tories are in big trouble.

Having said all that, in politics there are always exceptions. And there are two reasons to think that Starmer in 2023 may yet be that exception. Firstly, since 2015 the Labour party has not done well in local contests. Having gained thousands of seats when Blair and Miliband were leading the opposition, the party has gone backwards under both Corbyn and Starmer. Indeed the party has done so badly in local elections under Starmer that, unless he gains over 300 seats in 2023, he’ll still have fewer councillors than Corbyn bequeathed to him in April 2020. He has a mountain to climb, and in this case it is a mountain of his own making.

Secondly, Labour may be popular in polls but it is in poor shape organisationally – and you need to be organised to compete and win in the literally thousands of wards that are contested in local elections (compared to 632 British seats in general elections). Labour’s most recent accounts show that it has a financial deficit of £4.8m, compared to a surplus at the end of 2019; meanwhile, its paid-up membership has dropped from 480,000 in 2019 to 380,000 in 2023. In local elections volunteers are an essential resource, and Labour is in desperate need of them.

Having said all that, these are perhaps the best circumstances for the Labour opposition since 2012, when it benefitted from a collapse in Lib Dem support and the “Omnishambles” budget. The current government is widely disliked, the Labour leader enjoys decent approval ratings, the opposition is starting from a low base (having performed poorly last time) and they have a big lead in the polls. Though Labour’s poor local election record and organisational difficulties may slightly dent their expected results, they should expect gains of 200-250 seats (2-3%) at an absolute minimum. Anything less than that would be very underwhelming, given the context – and concerningly low for a party that many assume is on course for a landslide win in 2024.

In short, data from both the past and the present points to a sizeable local election victory for Labour next week, with 500+ gains being the result that an average opposition party should expect in this context. In a week’s time, we’ll know for sure if Labour has lived up to those expectations – or if Starmer has once again underperformed.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties

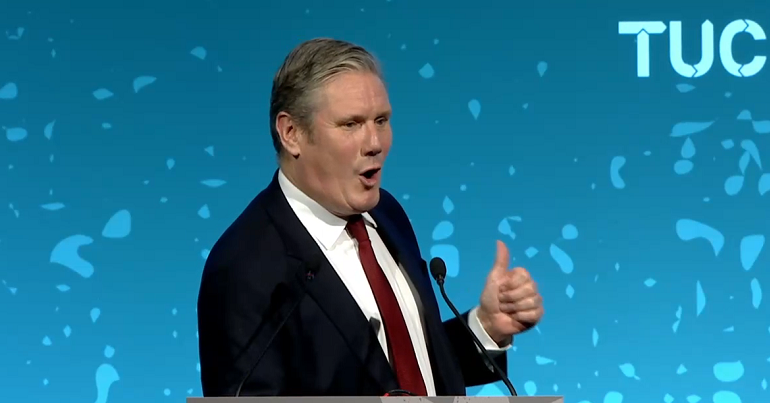

Image credit: TUC Livestream

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.