"The four-day week gives everyone the gift, the resource, the power, of time, of choice"

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote of economies suffering a “temporary phase of maladjustment”, as he predicted that once that was sorted out, over the next century, the standard working week would fall to 15 hours.

Sadly, his “phase of maladjustment” did not prove temporary. It continued for the next century.

Rather than seeing our economies work for people, deliver a better quality of life as productivity soared and technology delivered significant advances, we’ve seen the 40-hour, five-day week won more than a century ago continue, and even increase. Not only do workers slog away in their statutory hours, but pressure to respond to a bosses’ midnight email or the quick reaction to a social media post at any hour of the day or night is now the reality of working life for many, being effectively 24/7 being on call.

The UK has the second-longest working hours in Europe – behind only Greece – and having just returned from France and Italy, where working hours are far shorter and in France there’s even a law about not being forced to work out of regular hours, the positive impacts on quality of life, on family and community structure, are obvious.

Perhaps when it comes to the UK and US, Keynes didn’t sufficiently allow for the “Protestant work ethic” identified by Max Weber as a factor in the rise of capitalism. The religious aspect might have little relevance today, but there’s no doubt that in the UK and the US, there remains a strong moral pressure to be seen to be working “hard” – which usually translates into “long”. The blight of presenteeism means someone who works efficiently, productively, and leaves on the dot of their contracted hours may well find themselves being frowned on.

No one lies on their death bed and groans “I wish I’d spent more time in the office”, but living a balanced life, making time for friends, family, community and self, requires a strongminded determination not to go with the flow. The illogic of working long and hard to be able to afford the things that repair the damage done to body and mind by working long and hard – holidays, “pampering”, treats – is seldom examined.

But there is, happily, a real push on to finally start to deliver the progress Keynes foresaw, in a global campaign in which the UK is playing a significant part, to trial a four-day working week as standard with no loss of pay.

The group 4 Day Week Global is working in the UK, as well as the Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, with the think tank Autonomy and researchers at Cambridge University, Boston College and Oxford University to run a six-month trial, supporting a wide range of employers, from a fish and chip shop to a bank, a law firm and a cosmetics producer. And South Cambridgeshire Council looks set to be the first local authority to join them. Academics will be studying and charting the results, and the early signs are promising.

Joan Fielder, the CEO of Helping Hands, which provides support to the elderly, reflected on the early days of the trial: “It doesn’t take away from our service or commitment; instead it allows a better work-life balance and keeps us all focused and refreshed.”

It makes sense. We know the huge levels of stress, and mental ill health in our society, the pressures on many workers to provide family care for the young and the old, the time demanded to wrestle with the incompetence and chaos of our privatised, austerity-depleted public services and utilities, the widespread burnout across many sectors of our economy. We’ve seen the huge difficulty in maintaining communities as the retirement age has risen, two incomes have proved essential for households to keep a roof over their heads, and volunteers have been asked to fill in the gaps of depleted public services.

And employers are finding – in an ageing society with terribly poor public health and high levels of morbidity among the working age population – it extremely hard to find and keep staff. A four-day week is a signal that workers are being regarded as people, not robotised cogs in a machine, as well as a huge practical benefit.

Today in the House of Lords I have an oral question, asking the government of its view on four-day week. Given the government – of I assume Liz Truss – will be about two hours’ old at that point, I’m not really expecting a breakthrough. Although I’d expect contributions from the Labour and Liberal Democrat front benches in our short debate, and it will be interesting to see the stance they take.

It isn’t hard for me to explain the Green Party position. We’ve long been calling for a four-day working week as standard with no loss of pay. And I’ve long been pointing to the excellent work done by the New Economics Foundation on the idea of eventually getting to a three-day week as standard, pretty much the goal that Keynes could see in 1930.

Advertising and social pressures and government policies since Keynes have seen pursuing growth as the obvious goal for “progress”. That’s got us to the mess, environmental, social, economic, that we’re in today.

The four-day week gives everyone the gift, the resource, the power, of time, of choice. We can’t keep consuming more “stuff” – the planet won’t take it – but we can get more life. For people, society and planet it is win, win, win.

Natalie Bennett is a former leader of the Green Party of England and Wales. She now sits in the House of Lords.

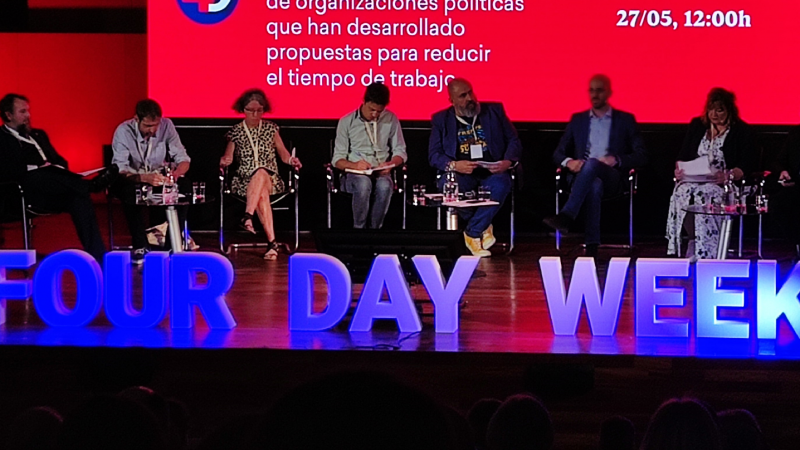

Image credit: Francesc Fort – Creative Commons

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.