How many times must a disappointed party berate or replace their leader before they realise the leader is not the problem?

Steve Melia is a Senior Lecturer at the University of the West of England.

Like many progressive voters I have watched the Labour Party’s infighting with growing frustration. It would be amusing, were it not for the corrupt one-party rule it is helping to entrench.

Five years ago, think tank Opinium published this report, which demonstrated the scale of the problem facing the left in the aftermath of the EU referendum. I wondered how long it would take for leaders and opinion-formers on the left to recognise the reality it revealed and draw the inevitable conclusions, which its authors stopped short of doing.

Their study divided the British public into eight ‘political tribes’ cutting across the traditional divisions of left, right and centre. Two of these tribes, ‘Our Britain’ and ‘Common Sense’ accounted for around half the population.

Their views, and their fundamental values, make it easier for one party, the Conservative Party, to win the 40% or so needed to secure a majority under the first-past-the-post system. The ‘Our Britain’ tribe held strongly protectionist, anti-European anti-immigration views, but 15% of these people described themselves as ‘left-wing’ and 19% of them voted Labour in 2015.

In a Guardian article, one of the report’s authors identified immigration as the key issue “uniting the right and dividing the left”; but the significance of immigration, like Brexit, goes deeper than the specific issue; it signals a difference of world-view: internationalist or protectionist. It should surprise no-one that the divisions revealed by the EU referendum are still with us.

The other six ‘political tribes’ in the study were smaller and more disparate, making it difficult, if not impossible, for any one party to appeal to all of them. Opinium found strong support for some left-wing economic ideas, such as taxing the rich and banning zero-hours contracts, spread across protectionists (the majority) and internationalists.

The big problem, which recent events have intensified, is that Labour, the Lib Dems and the Greens all appeal to voters with left-leaning economic views and an internationalist outlook. That combination is found amongst less than a quarter of the population. No party currently appeals to the left-leaning protectionists – leaving the field open for the Tories.

My perspective on this is influenced by the contrasting areas of England where I have lived. I spent my formative years in the Toxteth district of Liverpool then moved to Dagenham and Romford, then to affluent villages in Hertfordshire and Kent, a less affluent village in rural Devon and now Bristol West, a multicultural constituency with the highest concentration of PhDs in the country. I have made and lost friends across Britain’s widening cultural divide.

Some political commentators have now recognised that divide, but continue to urge Labour, and particularly its leader, to reach across and appeal to everyone. In discussing issues like immigration I began to realise that might not be possible. My educated friends in Bristol West find it difficult to understand how anyone who isn’t racist or ignorant could favour restrictive

immigration policies. They might acknowledge pressures on infrastructure and services, but would argue that if governments addressed those problems, opponents would come to accept, or even welcome, more immigration. I heard similar views expressed over Brexit.

Many people on the other side of the cultural divide (often, but not always, white and working class) find such attitudes patronising and offensive. Ed Milliband’s ill-fated attempts to paint Labour as a party tough on immigration illustrate the difficulties for any progressive party trying to bridge that divide. He alienated his own members and failed to convince anyone of his sincerity. The alternative, to paraphrase Owen Jones – be true to our values and working class voters will reward us – is starting to sound like wishful thinking.

So is there any way out for the left? Momentum’s recent decision to embrace proportional representation is a positive sign. An alliance to defeat the Tories (as advocated by Compass) is an essential first step, but it will not be the end of the process. More representative voting systems favour more representative parties.

We currently lack a working class socialist and protectionist party, an equivalent to La France Insoumise or Die Linke in Germany (though likely to be quite different in a British context).

I wouldn’t vote for them. Neither would many people in Bristol West. But a party of that nature would find it much easier to win back Hartlepool and Harlow without alienating its members or voters in other places.

Steve Melia’s latest book, Roads, Runways and Resistance – from the Newbury Bypass to Extinction Rebellion is published by Pluto Press.

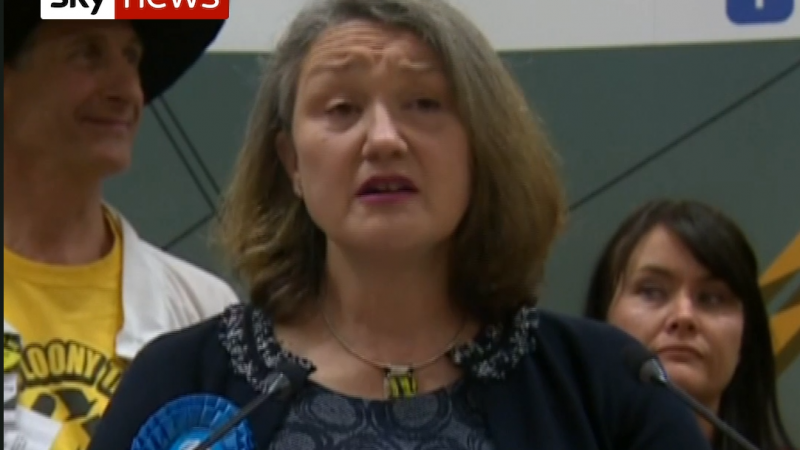

Pictured: Hartlepool’s new Conservative MP, Jill Mortimer

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.