Intellectual property law expert Alan Story says we must learn from the Polio epidemic.

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, another virus and another pandemic swept nearly unchecked across the world. At its peak, almost 500,000 people a year, including many children, died from or were paralyzed by the viral infection known as polio. It was – and is – a fatal disease with no cure.

Polio was all but eradicated in that era – and it provides us with some lessons as to how peoples and governments today can deal with coronavirus.

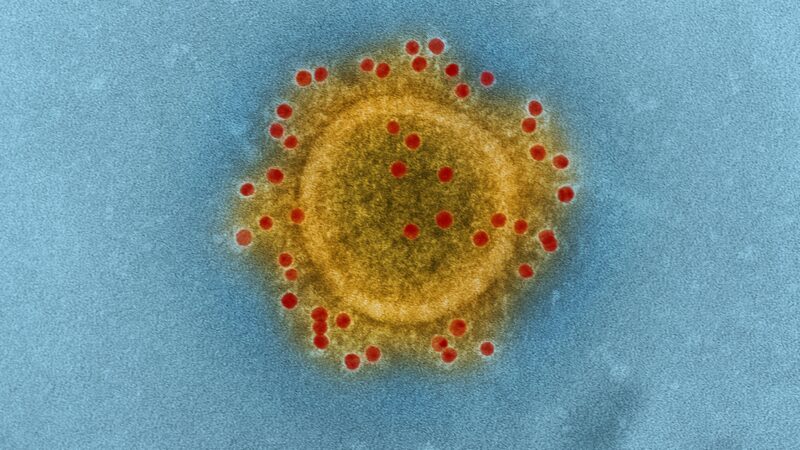

And the polio saga also challenges the claim of an academic commentator last week that we are in “unchartered territory” when it comes to developing vaccines to deal with such swift global killers. As of 7:00 on 13 March, 4934 people in more than 120 countries had died from coronavirus.

While a vaccine for coronavirus (or Covid-19) may still be 12 to 18 months away, it is certainly not too soon to ask: will such a vaccine be affordable and available to the millions across the globe who will need it? Not just in the UK but those countries without an NHS-style public health system?

More pointedly, as an infectious disease researcher was quoted as recently asking: “What matters more to the drug (pharmaceutical) companies?…Boosting the bottom line or taking a leading role in stemming the Covid-19 outbreak?”

Out of the media spotlight, it’s time to start asking whether a vaccine for coronavirus will be accessible.

Back in the 1950s, US physician and medical researcher Dr. Jonas Salk was worried what could be done to invent a vaccine for polio. In 1955, he and his team developed the Salk vaccine, as it became known, and, as a little nipper in school in the late 1950s, I still remember taking it – as did millions of other children across the world, with tremendous life-saving results.

“Who owns the patent in this vaccine?” Dr. Salk was asked in a 1955 television interview. His reply was inspiring: “The people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

Salk was quite correct to focus on the patent issue for pharmaceuticals. To grant a patent to the idea behind a chemical formula, and/or the method of manufacture means the state creates a monopoly private property right in that pharmaceutical.

As a result, the owner of the patent – usually a multinational such as Pfizer, Novartis, or GlaxoSmithKline PLC – is given the power to charge whatever it decides it needs and wants. And with the pharmaceutical sector regularly gaining a higher rate of return on capital than any other sector of the economy, what the sector deems it ‘needs’ often comes at a very high cost.

US economist Dean Baker has studied the politics and economics of the pharmaceutical industry for decades. In Chapter Five of his 2016 book Rigged, he explained in convincing detail that, while most pharmaceutical products are relatively cheap to manufacture and distribute, it is monopoly power of patents that makes them expensive, very expensive.

I lived in the US 25 years ago. I still remember how a woman in the queue ahead of me at a drug store (aka chemist) shelled out well over $US300 for a few of her prescriptions.

But the problems of this business model go far deeper. Writing last week on the barriers to finding a vaccine for coronavirus, Baker said that the research process for this vaccine “should get us angry”:

“We have people around the world working as fast as they can to develop an effective vaccine against this dangerous disease. That is great – except these people are working in competition, not in collaboration…

“Imagine how much faster the research would advance if these researchers were working in collaboration, sharing the results with others, and posting them on the web so the researchers throughout the world could learn from them,” Baker wrote.

The 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak had shown again that the global pharmaceutical development and distribution system was broken and totally profit-driven. Its priorities were all wrong. Developing “life style” drugs such as Viagra came first.

Enter, in 2017, CEPI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. Funded by public and private money, CEPI was tasked with financing and coordinating the development of new vaccines for infectious disease epidemics.

When CEPI launched, it initially had an “equitable access” policy for vaccines. But under pressure from Big Pharma and conservative governments, that policy was significantly weakened in 2018 and replaced by one that was not only “vague, toothless and weak” but also in “stark contrast to the original intent of CEPI” as Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) explained in 2019.

In recent months, CEPI’s board may have begun to change tack. In a March 5 2020 update, MSF said it was “cautiously optimistic about the future accessibility of CEPI-funded vaccines.”

As well in early March 2020, the UK announced another £20 million contribution to the CEPI coronavirus vaccine fund.

A memo to Health Secretary Matt Hancock: In 2018, Pfizer had profits of $US 11.1 billion, and its CEO took home an annual pay packet of $27.9m.

Learn from Dr. Salk. An accessible coronavirus vaccine would shine across the whole world. Don’t let them patent the sun.

Alan Story is a retired reader in Intellectual Property law.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.