Pubs, marches, local media and Facebook were used but canvassing wasn't.

Julian Critchley is the chair of the Isle of Wight Labour Party. He was its candidate in 2017 and campaign manager in 2019. With his permission, we are re-posting an article from his personal blog.

This article sets out the experience of the campaign from the perspective of one of the tiny handful of constituencies where Labour increased its vote. People already in shock about that actually happening probably need to sit down before learning that it was the Isle of Wight!

We didn’t win, of course. That’s for next time! But we did increase our vote and our vote share when Labour was losing votes and vote share pretty much everywhere else. We squeezed the votes of the LibDems and Greens in an election where the LibDems and Greens were not only increasing their votes nationally, but were being recommended as the tactical option locally by every one of those tediously irritating tactical voting sites.

So the result may not have shaken even David Cameron’s garden shed to its foundations, and nobody’s going to write a book about how the Isle of Wight Labour Party marched triumphantly from second place to, er, a slightly better second place. But this was an accomplishment which very seriously bucked the national trend nevertheless.

I don’t think the Labour Party, as it currently tears at its own entrails in grief, should leave any stones unturned in seeing how it might go about the next election better. And just off the south coast of North Island, the Isle of Wight is a particularly large and lovely stone to examine.

Firstly, I’ll set out what we felt were the main factors for our relatively successful campaign. I don’t think anyone will find these things particularly original or shocking. It’s just the basics of good campaigning.

Secondly, a little sting in the tail, because I’ll make some comparisons with campaigns in our top defensive and target seats, and those comparisons aren’t great. The party’s factional war has moved to a new battleground over whether the loss was the fault of the Right for forcing a change in Brexit policy, or the Left for installing Corbyn.

Yet there’s a “forgotten front” which is being neglected, which is that in some places, our campaigning appears to have been just not good enough. For those who want to skip to this bit and ignore the local campaigning bit, scroll on down to the sub-heading, you brutes.

Context – The Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight is the largest constituency in the country. It also happens to be considerably whiter, older and Brexitier (62% Leave) than most places.

We have no higher education institution, so few students. We’re short on public sector professionals and urban liberals, and any minority group you care to mention is more of a minority here than in most of the country.

We’ve also never had a Labour MP, or a Labour council. At present, we have no Labour councillors at all. In short, according to the various pollsters and their cunning “tribes” of voters, we’re the least promising territory for Labour you can imagine.

Yet in 2017, we doubled our vote, moving from fourth (yes, fourth) place behind Tories, UKIP and the Greens, to second place. This despite a ferocious tactical voting campaign by the Greens in which they outspent us by 100%, and which was supported by some of our own people on and off the island.

In the 2019 election, we raised our vote further, again in the face of unanimous recommendations from tactical voting sites for the Greens, in whose favour the LibDems had stood down their candidate. And of course we did so in the context of a national electoral disaster which saw Labour’s vote drop 8%, and rather more in constituencies with similar demographics to ours.

By demographics, we probably have to correct a misconception here. The Isle of Wight is not a wealthy place. It certainly has wealthy people, particularly older retirees. But as you can see from this chart, we’re actually quite similar to plenty of traditionally Labour seats. We are, in short, exactly the sort of place where the Labour vote dropped by a large amount on December 12th. Yet we increased our vote and our vote share.

As I wrote in my first blog in this series, the overall increase was relatively small. Brexit buggered us, as thousands of our 2017 Labour Leave voters left us. So that small increase masked our attracting a rather larger number of replacement voters.

I know that we’re all scheduled to be in the meeting marked “bitter factional warfare” for the next four months, but perhaps we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that not everything that happened in every constituency was beyond the ability of the local team to influence at least a little.

Now, to misquote Montell Jordan, this is how we did it.

Start the campaign early

We started our campaign for the 2019 election in June 2017. It was clear then that this was not a government which could last a full term, and many were predicting another election in months, not years. So while we certainly didn’t keep going at full campaign pace, we never fully took our foot off the gas.

Throughout the period we aimed to release one press notice every week, preferably about local issues, to get us coverage in the local media. When there are no local stories, there’s always a local angle you can try to national stories.

Demanding answers from the current Tory MP about why he voted this way was always a good way of ensuring that local voters knew that the Labour Party was holding him to account. Any local story about council or national cuts would also inevitably see a quote from Labour popping into every local editor’s inbox.

In addition, we aimed for an update to the party’s main shop window, our public Facebook page, every other day. By 2019, that was an update every day. This was very important because it built a page following which was going to be absolutely central to the 2019 campaign. We’ll return to this.

Not all the press notices were picked up. Not all the social media posts gathered lots of attention. There were fallow periods. But by the time this election was called, we had been making the biggest non-Tory noise locally for over two years. A good way of measuring our impact was the complaints from below-the-line Tories on local media about the local Labour Party getting too much coverage.

Get a good candidate

We had an excellent candidate. One of the advantages of being a below-the-radar seat is that we don’t attract ambitious careerists who can only find us on a map because of the clue in the name. Nor does central office ever consider imposing anyone. We get to choose freely.

After my run as accidental candidate in 2017, I decided at the last minute I didn’t want to do it again. This was fortunate for us, because it opened the door to Richard Quigley, a local small businessman with manic energy and no background (and therefore no baggage or enemies) in local politics.

Crucially, he also brought with him two key attributes. Firstly, he was genuinely committed to the policies of the party, which meant his answers were always authentic and convincing. Secondly, and unlike me, he genuinely appears to like people. I don’t understand that, but it certainly worked for us.

I don’t want to overegg the importance of the candidate. After all, every political party could draw up a long list of incompetents, crooks, sociopaths and fools who have nevertheless been elected, and a similarly long list of wonderful, worthy, committed saints who haven’t got anywhere. But in an election where it often felt like people were looking for reasons not to vote for us, the fact that our candidate persisted in only giving reasons to back us was an enormous help.

Win the real-world visibility war

In 2017, I’d often had received the comment “I didn’t know Labour was active on the island”. We needed people to see us as not just a viable party, but the biggest. Simultaneously, we knew early on that we would be fighting something which I know other CLPs experienced: shame.

The “othering” of Corbyn had long extended past him alone to encompass the entire party. To support Corbyn’s Labour was, according to most of our national media, somehow beyond common decency. We knew this had happened before the campaign started, and one of our earliest priorities was to create a safe space for supporters.

Not many people are brave enough to put their heads above the parapet when bullets are flying, if they’re on their own. But give them a few visible comrades willing to go over the top alongside them, and that can change. Signage was the offline half of the battle to create a psychological safe space for potential Labour supporters to feel that they weren’t alone, and there was a point in their support and their vote.

We prioritised the ordering of signs, boards and posters, and set up an efficient manufacture and distribution method. Then we emailed all 850+ members every other day throughout the campaign with a central contact point for signage. We would almost always get signs to requests within 24 hours. We also specifically targeted the (very expensive) garden signs on the streets with high traffic. Cul-de-sacs in the middle of the countryside got a window poster. The last sign was put up late on December 11th in a street which was used to go to a polling station. In total, we put out 240 garden signs and 750 A3 window posters.

We also printed 30,000 leaflets with local printers, in addition to the 76,000 freepost leaflets which slowly – oh so very, very slowly – were printed by the national party. The leaflets had a mini poster on the reverse, so we were also effectively giving out 30,000 more window posters for cars and homes.

None of this is rocket science, but it’s a vital building block. There was unprecedented intimidation, abuse (and destruction of signage) in this election. We needed to show our potential supporters that we were out there with them in force.

Maximise activist efficiency

This was an early decision to repeat what we didn’t do in 2017. We didn’t canvass.

It’s a case of maths. Every CLP will know that the ratio of members to activists is not great. Our 850 members yields about 100 who will attend meetings, 50 who’ll deliver leaflets and help out, and 30 who are confident and comfortable talking to voters face to face. Of those 30, all will hand a leaflet out in a town centre, but only a dozen or so are really up for the intensely intimidating business of knocking on a stranger’s door in the dark and asking them to vote Labour.

I’ve done it. I hate it, but I’m quite good at it. When excluding houses with no answer, and those who say “no thanks” immediately, I reckon I end up having about 8-10 actual conversations in an hour at my very best, and 75% of them will be already committed voters for us or someone else. So maybe 2 or 3 actual undecideds an hour. If all 12 of our willing canvassers were able to turn up at the same time, we’d maybe get 20-30 undecided conversations in an hour. We have an electorate of 113,021, living in an entire county of 76,000 houses in over a hundred different towns and villages spread out over 148 square miles.

So we didn’t canvass.

But we still needed to have those conversations and, above all, win the visibility war. So while our opponents were trudging a fraction of the island’s streets, unseen, we were in the town centres.

With the less in-your-face intensity of doorstep canvassing, we had more bodies willing to stand in town centres, hand out leaflets and engage in conversation. On each weekend, we had people out in most or all of the six major population centres on the Island, very visibly wearing red and handing out our leaflets. We were seen by thousands more people who we could have reached canvassing, in more places.

The cherry on the top of the visibility cake was the ‘March For Labour’. Fifty activists were involved in an event where most walked the 7 miles between the two main towns of Ryde and Newport. All decked out in red, carrying banners, this wasn’t an attempt to pay homage to Mao’s Long March. It was done because it took us along the busiest road on the island, where we were seen by many hundreds of cars over a four hour stretch, as well as many hundreds more people in both Ryde and Newport.

And it was an odd enough event that those people spoke to other people about seeing these red-clad nutters marching down the road getting beeped by passing cars. As well as demonstrating commitment, it demonstrated numbers and strength – no other party could put something like that on. It also was unusual enough to allow us coverage in the local media, but more on that later.

There are rituals in elections – doorstep canvassing is one, standing outside a polling booth with a clipboard is another. These can make sense if you’re in a tight marginal and have the numbers of activists to not only find out where your vote is, but to get bodies round to encourage it out on the day. Few constituencies have that capacity, yet many which don’t probably still perform the rituals. It’s a good idea to review those actions to see whether more bangs for the activist buck can be had elsewhere.

Go to the people, don’t make them come to you

The local Green Party hired a shop in Newport for the campaign. It must have cost them a packet. We took our candidate to the pub. Lots of pubs.

We knew we couldn’t wait for people to come to us, we had to go and find them. So we organised multiple meet-the-candidate events, which we promoted, in pubs. The pubs liked it, because of the cash behind the bar. The local members liked it, because they could chat to the candidate (and drink). And we got noticed by, and spoke to, people who would never have dreamed of walking into a political party’s shop.

We weren’t packing them out like a Corbyn rally, but it was another way of being visible, or providing a safe space, and of accessing real-life networks of people who used the pubs. Even if they didn’t talk to us, they saw us, and they talked about it to their mates. Word got around. Labour were out and about, and down the pub.

The candidate also visited care homes and cafes, specifically to meet and listen to (note listen to, not talk at) important local subsets like care workers and small businesspeople. Even where there might only be half a dozen attendees, we would then see one or more of them in a neutral online space saying “I met that Labour guy, and he was really nice…”. There’s a multiplier effect from each event. We kept the candidate busy.

Fight for local media

Slightly bizarrely, our local media was less willing to cover press releases from us during the campaign than it was before the election was called. We were told by one editor of a local online news source that press releases during the election were “just campaigning, not news”.

It rapidly became clear that the local media didn’t see it as their job to communicate policies to the voters. Our original plan to issue a press notice from the candidate every day linked to the daily campaign briefing from HQ was quickly abandoned after the first 7 or 8 were universally ignored.

As a result, our attempt to communicate our policies shifted to our own online resources, which I’ll deal with in the next section.

But the local media still had a role to play. It reached parts of the electorate which we couldn’t reach directly online, particularly the more elderly section of the population who read the print versions. And not just the two county newspapers, but the monthly periodical which is delivered to every house on the island. We quickly bought and arranged advert space in all of them. Adverts are no substitute for coverage, so we had to manufacture some.

I’d love to tell you we were cunning enough to plan it all, but mostly it was about being fleet-footed and seizing opportunities. The Tories did us a favour by writing a public letter to us asking us about Brexit which the media covered, along with our reply.

Clearly it was designed to promote their central campaign message, but sauce for the goose etc, so we returned the favour with a letter about the NHS. These letter exchanges, though ritual, not only allowed us to promote our key message, but also reinforced the message that this was a red-blue election, causing real harm to the tactical voting campaign of the Greens.

Various other opportunities presented themselves. Tory loon Suella Braverman announced on TV that there was going to be a new hospital on the Isle of Wight (there isn’t). Our own Tory, Bob Seely, announced Labour planned to shut down the local Free School (we didn’t).

We got a tip-off about a night of chaos in the local A&E. The key was being able to respond very rapidly. In all cases we had press notices out in a couple of hours maximum, and we followed that up with phone calls to the journalists to exert a little persuasion to run the story. We adapted quickly to the stance the local media chose to take, and continued to get coverage.

Win the Online War

It’s hardly a revelation to say that the online world has become the crucial battleground of 21st Century campaigning. Even on the Isle of Wight, where we only recently stopped believing electricity was witchcraft. We knew that this was where we had the best chance of getting our message across to a largely disengaged electorate, untainted by media bias. It became even more vital when the local media chose to abdicate the role of communicating policies.

Targeted local material

Fortunately, we were ready. I mentioned earlier that we had been preparing since 2017. We had focused on Facebook. It has greater reach into the non politically-committed electorate than other social media, and it’s the most important platform for the age profile of the Island.

From the end of 2017, we maintained our public Facebook page as a shopfront for the local party. It was not a free-for-all forum filled with interminable trollish arguments, or a CLP noticeboard of no interest to anyone but the CLP. It was a sales pitch. It needed to be relatively professional and relentlessly positive. It also needed to be updated frequently so that it regularly pushed our news into other accounts, as well as becoming a place which our hundreds of Facebook-using members checked regularly and shared from.

We had observed what “sold” from the Facebook page over the previous two years. Which stories always did well (ferries and the local NHS, since you ask), and which did little trade (national-only issues, and issues which affected relatively small sub-groups of the local population). Video clips and catchy picture memes were shared many times, walls of text weren’t. There’s nothing radical about these observations, which is why the upcoming comparison might shock a few readers.

So we set out at the start of the election to ensure that there was a distinctive local flavour to as much as possible. Memes badged with the Island Labour logo were produced for national policy announcements, with text on how they’d affect us. Eyecatching shareable digs at the local Tory MP or council were created. And we produced a series of short, snappy videos of our candidate which looked and sounded authentic (because they were – I filmed them on my phone while his dog tried to get in the shot).

The results can be seen here:

The full page

The pictures and memes

The videos

The point was that much of the material was seen as locally relevant, because we’d produced it, twisted it to local issues, and branded it locally. This was a very specific conversation which Island Labour was having with Island voters, in the midst of a national election.

Use your people’s networks

Of course, no amount of excellent material is of any use if people don’t see it. So we encouraged our online membership daily to share material from the main page. If each individual member has 200 facebook friends, you only need 20 of them to share your meme, and you’ve just reached a potential 4000 voters. Then some of them share it further, and so on.

Some statistics give you an idea of the impact. Over the four weeks of the election, we reached more than 118,000 people. More than 72,000 “engaged” with one or more of our posts, meaning they reacted to it, clicked on the link, shared or commented. 9 of our posts reached more than 20,000 people each. 32 posts reached more than 4,000 people. Even allowing for duplication, these are big numbers, reaching places in our electorate which nothing else could get to.

One way we knew we were reaching the parts of the electorate we didn’t normally reach was the huge spike in abusive messages from Brexit Party and Tory supporters. They were seeing our material repeatedly, because it was being shared into their facebook feeds either directly or indirectly. Although I won’t claim it was pleasant wiping the virtual right-wing spittle from our comments page twice daily, I was conscious that every illiterate troll whose comment was hidden meant we were reaching more local voters.

This was just the direct social media. We produced a section called “helpful memes”, which allowed our members and other sympathetic users to copy the pictures and paste them on elsewhere. During the campaign, I saw numerous memes which originated with us being shared in the “neutral” social media community pages around the island. These wouldn’t count on our direct statistics, but were still part of our online marketing, and a very effective part. Posts on neutral ground from people who weren’t well-known local Labour figures had greater value because of their perceived authenticity in peer-to-peer networks.

So, back to the stats, which I watched like a trainspotter with OCD for the duration. The first two weeks of the campaign, we pushed from our usual weekly c5,000 engagement numbers up to 20,000 per week, and then carried on going. For the last two weeks of the campaign, we averaged over 20,000, and the final week was 28,400 engagements (likes, comments and shares).

Our Green opponents, competing with us to reach the Remain voters in the constituency, were always far below us, spending much of the last two weeks at 25-33% of our engagements, while the Tories only learned how to play with Facebook in the final week, and managed to creep up to 9,000 by the end. Our main rival was actually Stephen Morgan’s excellent online campaign just over the water in Portsmouth South. We had clearly surpassed him by the last week, right up until the final day, when through some dastardly magic he suddenly rocketed past us, the swine.

The National Comparison – this is the bit for those looking for controversy

Why am I telling you this? Well here’s some tables which will make grim reading for Labour supporters.

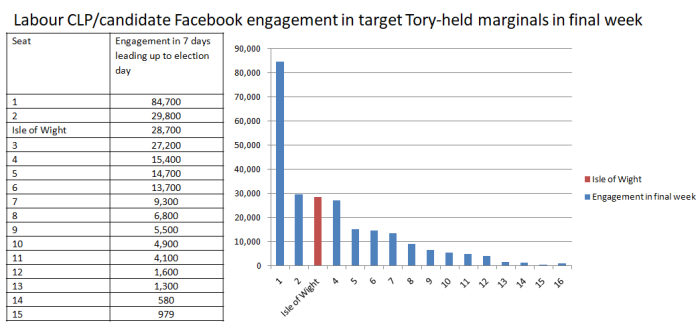

On election day, before the result, I visited the facebook sites of our main English defensive and offensive marginal seats, and used facebook’s comparison ‘Insight’ tool to look at their levels of engagement. Sometimes there’s both a candidate and a CLP page for a constituency, and I’ve chosen the biggest one of the two, where that’s the case. Here’s the table for marginal seats held by the Tories which we had to win.

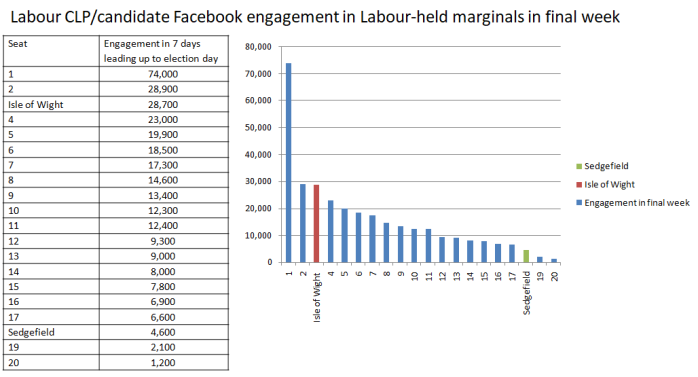

Here’s the data for our most marginal defensive seats (except two)

Those graphs tell a story. For all that I am proud of our efforts here, I’m astonished that our small band of amateurs in a historically safe Tory seat, with no paid staff, and no assistance from the regional or national party, should have been running a bigger facebook campaign than all but two of our top target seats, and all but two of our most vulnerable defensive seats. In some instances, our online engagement was literally more than twenty times the size of that in seats which had tiny majorities.

I didn’t understand how this could be the case, and so I went and looked at these pages to get a qualitative feel for what the quantitative data was telling me. In too many cases, the picture was grim. No memes, no positivity, no clips. Nothing that would entice people to share and spread the message. In several cases there weren’t even any policies.

What I saw far too much of, was a simple picture of the candidate standing with the same half dozen people on a different dark, cold street, holding leaflets and trying to look as if they wouldn’t rather be anywhere else. Occasionally, there’d be a picture of the candidate next to a celebrity politician (David Miliband seemed to get around a few of these places), or even just a celebrity (and so did Ross Kemp). But the statistics were terrible. Nobody was sharing it. Nobody cared. Nobody knew.

I was also struck by how many times I was seeing the same handful of people in those endless pictures of leafleting. Meanwhile, I was aware that we had involved dozens and dozens of enthusiastic activists in our various activities. The contrast was stark.

I scrolled as far back as 21st November on one candidate’s facebook page, covering the last 3 weeks of the campaign, and found not one single post about any Labour policy in this election. Not one. Just pictures of the candidate and the same handful of leafleters, plus a couple of the candidate and a couple of grandees. Their engagement rate was less than 10% of ours. In a heartland seat with an immense Labour tradition. This pattern repeated itself in others.

It may well be that the seats in question (which I have anonymised to save blushes), had absolutely superb offline campaigns. But that’s not an excuse for missing this battleground. Online campaigning in 2019 is absolutely vital, particularly on facebook. In some of our most marginal seats, we were essentially doing very little of it.

Local campaigns matter

This is conjecture, but I’ll put it out there anyway as a contribution to the debate raging about this election. We in the Island were able to run the campaign we did because we have, by and large, embraced and encouraged the new and enthusiastic post-2015 members. Our Corbyn-sceptics stayed on board, and while they may not have been the most active local members, they did their bit, to their enormous credit.

That energy and genuine enthusiasm meant people gave up their time and skills freely to help. It also meant that our candidate, and the core campaign team, were all unashamed and enthusiastic about sharing the policies and promoting the party.

The picture I saw online in several “heartland” marginals gave a very different impression: of candidates who couldn’t bring themselves to promote their own party’s policies; of hollowed out CLPs with only a handful of members left who are enthusiastic or daft enough to repeatedly go and stuff letterboxes for the candidate; of a sales team who had no faith in what they were selling.

I don’t think one has to be a marketing executive to know that it’s hard to sell a product when your shop window is empty, you’ve got no salespeople, and your pitch is telling your intended customer that they shouldn’t buy what you’ve got.

Any visiting alien looking online would have assumed that the Isle of Wight was the Labour heartland, not the “red wall”. There are questions to be answered by some CLPs, as well as regional and national office in terms of the support they offered the marginals.

Those seats may not have been won anyway, but I can certainly say that it seems more could have been done to try, at least online. In some cases, I would suggest that those seats’ fate was sealed even before the campaign: too few bodies, too little groundwork since 2017, not enough energy.

As a final note, I added Sedgefield in my graphs, despite not being one of the top marginals, because an awful lot of press coverage has been given to the fall of Tony Blair’s old seat. Maybe its loss was inevitable.

However, the online campaign there managed to engage less than 20% the number of people we reached on the Isle of Wight. There are now more Labour voters on the Isle of Wight than there are in Sedgefield – now that’s a quote which should have a few Labour legends spinning in their graves. We worked very hard to win every single one, and we increased our vote.

Just because we could, doesn’t of course mean that everyone could, of course. We had a decent-sized LibDem/Green vote to squeeze from 2017. We were the insurgent, not the target, which allows for an aggressive, rather than defensive campaign. There was little pressure on us beyond the pressure we placed on ourselves. And the Isle of Wight is lovely, even in the winter, so it’s always a pleasure to be out and about (this advert was brought to you by Visit Isle of Wight). On the flip side, we had no paid staff, no external assistance, little history, and fewer of the demographic groups which are providing the new bedrock of Labour support.

I don’t think we did anything startlingly original. Other places also did some or all of the same things. However I’m struck by the way both sides of the Solent, in Portsmouth South and on the Island, bucked the national trend by running similarly energetic online and offline campaigns.

There are many lessons Labour needs to learn before the next election. One of them may well be that we have to fight every constituency as hard as Portsmouth South MP Stephen Morgan did, or as we did, or ‘safe’ seats can quickly become rather less safe than we might have thought.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers and to make the biggest impact we can in the next general election, we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 124 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.

33 Responses to “How Labour increased its vote share in the Isle of Wight against the odds”

Plain Citizen

Brilliant performance and superb article. Shame it’s unlikely to be read by anyone in Labour HQ.

richard malim

Nothing compared to the swing of 6.47% in (the miracle of) Bradford West

Thorntonite

You got 24% and were thrashed… this is delusional Bollocks of the highest quality PMSL!!

Julian Critchley

I think you’ve missed the point, Thorntonite.

If the Labour vote went down by an average of 8% across hundreds of constituencies, then there may well be something to look at in one of the tiny handful where the vote went up.

Nobody’s claiming that simply repeating this exact campaign elsewhere would have had the same result everywhere. However, we have seats which were lost by a few hundred votes after majorities of 8-10,000 were removed, yet where the online campaign was less than 10% of the size of the online campaign in the IoW, where Labour’s vote went up.

Could *some* of those seats have been saved with similar attention/energy in campaigning? It’s not impossible. It’s even likely. In any review of how we do things next time, we don’t have the luxury of retreating to a factional interpretation which seeks to use the available data only to confirm pre-election beliefs. No stone should be left unturned.

Barry Edwards

No-one should be canvassing during an election campaign. The time to canvass is between elections, when people are not expecting a knock on the door from a political party. (We knew we were making progress when the response changed from “We never see you around here” to “Not you again!”)

Try to get round the area over a four-year cycle, probably with a petition about some local issue and always have a ‘sorry we missed you’ card for the doors with no answer. Then your effort during the campaign is targeted at getting out the votes of the known Labour supporters and the doubtful. You know which doors are a waste of time.