The report found that ‘decades of failure’ by central government to stop the spread of combustible cladding combined with the “systematic dishonesty” of multimillion-dollar companies whose products spread the fire, had contributed to what happened.

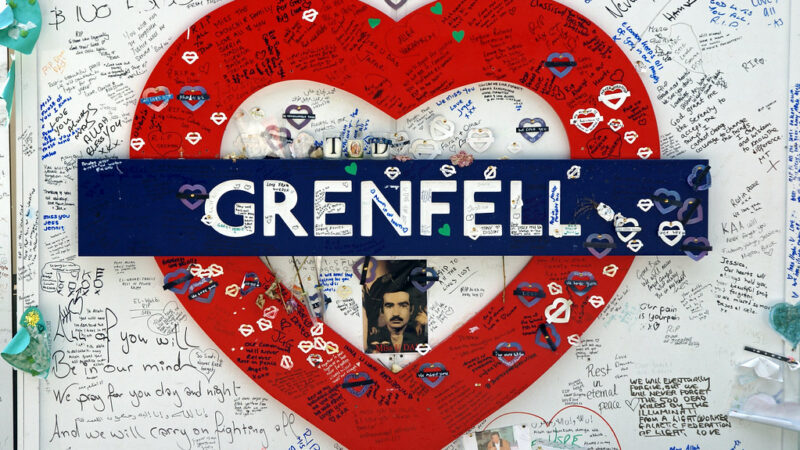

Today saw the official inquiry into the Grenfell disaster publish its final report, which found that ‘systemic dishonesty’ contributed to the horrific fire.

Seven years after the fire, in which 72 people died, the 1,700 page report found that ‘decades of failure’ by central government to stop the spread of combustible cladding combined with the “systematic dishonesty” of multimillion-dollar companies whose products spread the fire, had contributed to what happened.

So what are the key takeaways from the report?

1.Government ignored crucial warnings

The report found that the government was well aware of the risks posed by flammable cladding but failed to act on what it knew. Looking at government failings, the report states: “In the years between the fire at Knowsley Heights in 1991 and the fire at Grenfell Tower in 2017 there were many opportunities for the government to identify the risks posed by the use of combustible cladding panels and insulation, particularly to high-rise buildings, and to take action in relation to them.

“Indeed, by 2016 the department was well aware of those risks, but failed to act on what it knew.”

2. ‘Systemic dishonesty’ about panels and insulation

The report is also scathing about those who made and sold panels and insulation products, which it accused of ‘systemic dishonesty’.

It states: “One very significant reason why Grenfell Tower came to be clad in combustible materials was systematic dishonesty on the part of those who made and sold the rainscreen cladding panels and insulation products. They engaged in deliberate and sustained strategies to manipulate the testing processes, misrepresent test data and mislead the market.”

The report singled out Arconic Architectural Products, which it said “deliberately concealed from the market” the true extent of the danger of using its Reynobond 55 PE rainscreen panels which were installed on the external wall of the tower. It was also critical of Celotex, which manufactured the combustible RS5000 foam insulation. It said the company “embarked on a dishonest scheme to mislead its customers and the wider market”.

3. ‘Deregulatory agenda’ within government saw safety matters ‘ignored, delayed or disregarded’

The report was also critical of a ‘deregulatory agenda’ within government which saw safety matters ignored.

The report stated: “In the years that followed the Lakanal House fire the government’s deregulatory agenda, enthusiastically supported by some junior ministers and the Secretary of State, dominated the department’s thinking to such an extent that even matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded.”

4. Managing fire safety was seen as ‘an inconvenience’ rather than a priority by the tower’s landlords

In yet another scathing assessment, the report found that ‘there was no adequate system for ensuring that defects identified in fire risk assessments were remedied effectively and in good time’.

The council – the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) and the landlord organisation – the Tenant Management Organisation (TMO) were jointly responsible for the management of fire safety at the tower.

The report states: “The TMO developed a huge backlog of remedial work that it never managed to clear, a situation that was aggravated by the failure of its senior management to treat defects with the seriousness they deserved.

“Indeed, on one occasion senior management intervened to reduce the importance

attached to the implementation of remedial measures. The demands of managing fire

safety were viewed by the TMO as an inconvenience rather than an essential aspect of its

duty to manage its property carefully.”

5. Conflicts of interest

The report also found a conflict of interest between approved inspectors and those they were inspecting.

The report states: “One of the causes of the inappropriate relationship to which we have referred was the introduction into the system of commercial interests. Approved inspectors had a commercial interest in acquiring and retaining customers that conflicted with the performance of their role as guardians of the public interest. Competition for work between approved inspectors and local authority building control departments introduced a similar conflict of interest affecting them.”

Basit Mahmood is editor of Left Foot Forward

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.