'The last twelve years of cuts in public spending, have failed to deliver economic growth, prosperity, or resilience to household budgets.'

Prem Sikka is an Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of Essex and the University of Sheffield, a Labour member of the House of Lords, and Contributing Editor at Left Foot Forward.

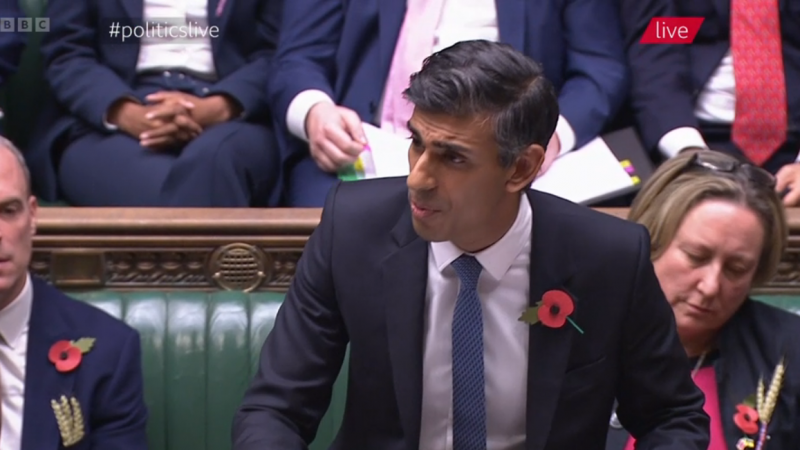

On 17th November, the UK government is set to present its second budget in just over seven weeks. For the last twelve years, the economy has been scarred by the government’s obsession with turning the UK into a low-wage economy with a docile workforce, making it fit for exploitation by footloose capital.

Public services, wages, pensions and benefits have been cut in real terms. Nearly 10 million adults and 4 million children have experienced food insecurity. Teachers, nurses, firefighters and police are relying upon food banks for survival. Every hour, ten people die in poverty. Some seven million people in England are waiting for a hospital appointment.

The UK is the only G7 economy still smaller than the pre-Covid level. Its GDP will shrink further as it is heading towards the longest economic recession since the 1930s. Unemployment is expected to double by 2025. The government needs to boost people’s purchasing power, invest in new industries and public services, but that is not its priority. Leaks from the Treasury suggest that a government chastised by markets is likely to impose £40bn-£50bn of tax increases and/or cuts in public spending.

The government that has handed £895bn of quantitative easing to speculators and in mid-October conjured up another £19bn, this time to bail out government bonds is indeed capable of creating money to support economic revival. However, the political will is not there. Tax and spend is now the dominant mantra. So, here is what it can do.

It can release billons by curbing frauds and tackling tax avoidance. Even before the Covid pandemic, the annual frauds in government departments were running at between £29.3bn and £51.8bn, equivalent to between £352bn and £622bn over the last 12 years. The government handed out furlough support, Covid loans and contracts without due diligence checks. Consequently, £219bn of the £387bn expenditure has been classified as “having a high or very high fraud risk”. The government’s efforts at curbing fraud have been so puny that in January 2022 a Minister resigned during a live debate on the Lords and said that the Treasury “appears to have no knowledge or little interest in the consequences of fraud to our economy or our society”.

In January 2022, the Department of Health stated that “there has been a loss in value of £8.7 billion of the £12.1 billion of PPE purchased in 2020-21”. More recent estimates are not known.

Fraud and waste is not the only drain on the public purse. HMRC says that each year it fails to collect between £32bn-£34bn of taxes due to avoidance, evasion and errors. Other models estimate the lost taxes to be between £58.6bn and £122bn a year. Altogether, taxes between £400bn and £1,500bn have not been collected because HMRC is starved of resources and the government has failed to check avoidance and evasion.

Unchecked fraud, waste and tax losses have brought the UK economy to its knees. The government’s response has been to hike taxes, especially on the poor. The poorest 10% of households pay 47.6% of their gross income in direct and indirect taxes, compared to 33.5% by the richest 10%. The government needs to recalibrate tax policies to boost the spending power of the poor and fund public services.

Its May 2022 windfall tax on oil/gas companies was poorly designed. Despite record profits, oil and gas companies are able to dodge not only the windfall tax, but also corporation tax. A redesigned modest windfall tax on energy companies can raise £40bn. A windfall tax also needs to be levied on banks and supermarkets making excessive profits.

The tax system rewards speculators and rentiers. Earned income is taxed at rates between 20% and 45%. In contrast, capital gains accruing to those selling second homes or dabbling in antiques, arts, securities, commodities and other markets are taxed at rates between 10% and 28%. Dividends received by residents in the UK are taxed at rates between 8.75% and 39.35%, and no tax is deducted at source from dividends paid to foreign investors. By taxing capital gains at the same rates as earned income and levying national insurance on the recipients can raise around £25bn each year. Another £12bn-£15bn can be raised by taxing dividends at the same rate as earned income.

Currently, national insurance is levied at the rate of 12% on annual taxable income of up to £50,270 and only 2% above that. By extending the 12% rate to all incomes, some £12bn-£15bn can be raised. Of course, the government can recalibrate the rates to ensure that the richest pay more.

In addition there are numerous other choices. For example, a wealth tax on the ultra rich can raise billions, as can a financial transaction tax upon speculators.

There is no economic case for austerity or increasing taxes on the masses. The last twelve years of cuts in public spending, have failed to deliver economic growth, prosperity, or resilience to household budgets. A new paradigm based upon redistribution and public investment is needed and billions are available to achieve that.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.