"Voters need to know why the government have made bad choices, and what Labour would do instead, not just that Labour would be a more trustworthy and competent administration, important though that is."

Mike Buckley is the director of the Independent Commission on UK-EU Relations and a former Labour Party adviser

Labour has opportunity.

The public’s decision to in large part give up on Boris Johnson is harming his party’s poll rating, albeit perhaps not as much as might be expected given Partygate and Johnson’s lies to Parliament.

More broadly, bad economic news on a daily basis reinforces the idea that the government is failing in its core purpose: to create and sustain a healthy and growing economy, manage public services, unify the country and take it in the right direction, and tackle long term challenges including climate change and social care.

Bad economic news extends from the micro – rising inflation and food prices at rates not seen the 1970s, both a byword for a struggling economy and bad governance – to the macro, with the OECD suggesting that the UK will have the poorest economic performance of any G20 country other than Russia in the coming year.

While at least some of the causes of the struggling economy are global – other nations are fighting inflation too – in Britain they’re worse. Our inflation rate of 9% far outpaces that of the Eurozone and US.

Public services continue to struggle with lack of funds and, increasingly, crippling labour shortages, also experienced by much of the private sector including hospitality, transport, farming and the automotive industry.

How the government is failing

The government is failing too on its own terms. Levelling up has failed to become a programme more than a slogan. Brexit – in part due to the government’s choice to continually stoke a fight with the EU over the Northern Ireland Protocol – is far from done.

Promised public services improvements including 20,000 nurses, 10,000 police officers and 40 new hospitals, remain undelivered. Action on carbon reductions and social care is stalled.

The list of crises may be long and growing, but Labour will not automatically benefit. To do so it needs to ensure the public understand that Conservative governments of the last 12 years are the primary cause of our multiple systemic crises. It needs too to articulate a clear strategy that gives the public confidence Labour would do a better job.

There are good reasons for oppositions to avoid setting out their programme too early in a parliament. The incumbent government may steal your idea if they think it’s a good one, as Rishi Sunak did with Labour’s windfall tax. Many voters only pay attention to politics closer to polling day.

Yet it is not just commentators who are asking for more clarity over what a Labour government would do for the UK, voters are asking too.

Voters need to know why the government has made bad choices

There is credence to the criticism that Labour has focused too strongly on criticising the government’s competence and integrity above criticising its programme.

Voters need to know why the government have made bad choices, and what Labour would do instead, not just that Labour would be a more trustworthy and competent administration, important though that is.

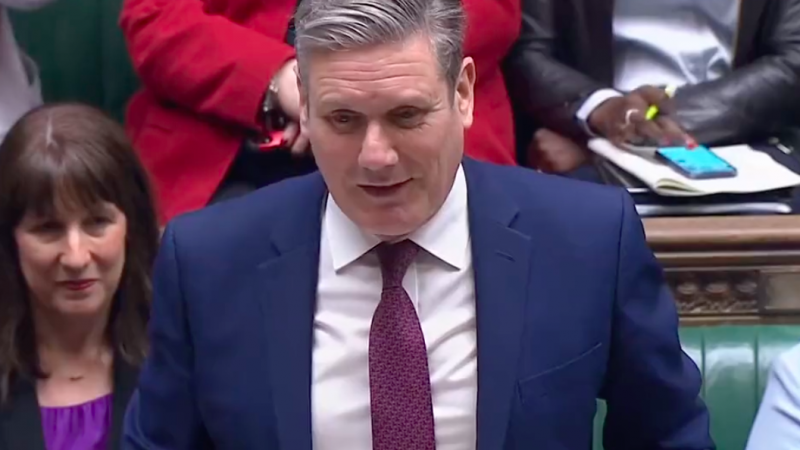

Keir Starmer needs to “come up with something that’s believable. But he doesn’t. He just has a go all the time,” one Wakefield voter told the Guardian this week. “He’s a criticiser, not an action person,” said another.

Action is hard from opposition but setting out what action a Starmer government would take on the cost of living, the climate crisis and Ukraine is perfectly possible.

It is not as if Labour does not have ideas. Rachel Reeves, Labour’s shadow chancellor, for example, has set out a raft of policy, much of which has been well regarded. But it is not yet linked into a wider vision of what Labour in power would be, or repeatedly pushed by the party as a whole.

Why is Labour caught in this bind?

One reason is its reluctance to criticise Johnson’s hard Brexit despite it being the heart of the government programme and a central cause of the country’s poor economic performance compared to its peers, which contributes to the severity of the cost of living crisis.

This is reminiscent of Ed Miliband’s failure to criticise Cameron and Osborne’s austerity from 2010 to 2015. That policy, much like hard Brexit, was economically ruinous for the UK and particularly harmful for poorer regions and demographics. Yet Miliband approached the 2015 election promising he would be stick with austerity even while understanding its harms.

Accepting your opponent’s premise is a poor way to do politics. It adds credence to their strategy and prevents getting a hearing for your own.

As evidence grows of Brexit’s harms – the Resolution Foundation for example has just found that Brexit’s “aggregate effect will be to reduce household incomes as a result of a weaker pound, and lower investment and trade” – Labour will be forced to speak out.

Doing so does not mean calling for Brexit to be reversed. Few believe that is politically possible, nor is it necessary to dramatically reduce Brexit-caused harms not just to the economy but also to sectors including security and defence, healthcare and science collaboration, all deeply harmed by the same inadequate agreements put in place by Boris Johnson as we left the EU.

As well as seeking to reduce harms Labour’s policy should seek to unify the country, just as Johnson seeks to divide it.

The policy of ‘a new deal with Europe’, which encourages cooperation and closer ties with Europe, is acceptable to both Leave and Remain voters, and is only unacceptable to a small minority of voters on both sides, says a recent report published by the LSE.

In coming years both main parties will end up with a version of this policy. Once Johnson is gone the Conservatives will revert to a less hard-line policy towards Europe. Bridges – both economic and diplomatic – will be rebuilt. The economy will demand it, as will politics given younger voters are for the most part pro-European.

Labour should get ahead of the game, using the opportunity to denounce Johnson’s deals as inadequate and their consequences as deeply harmful to the UK economy and our global standing.

The result would be a clearer criticism of this government’s programme and its failures, and open space for Labour to set out its own vision for Britain.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.