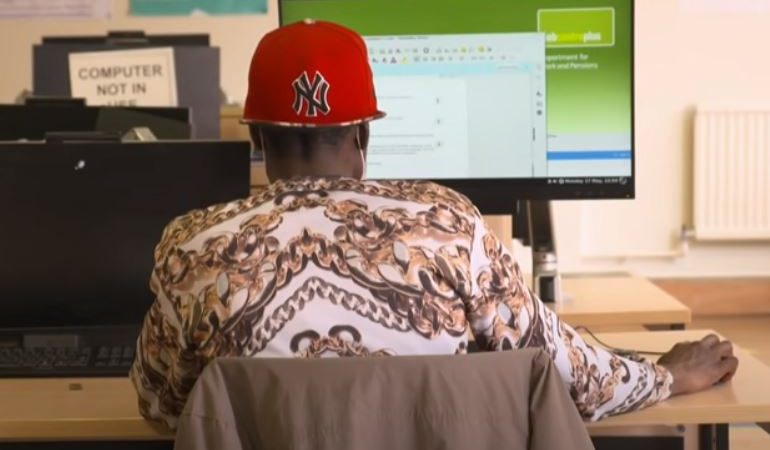

‘Despite decades of racial equality laws, there are still disturbing racial patterns of employment.’

Prem Sikka is an Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of Essex and the University of Sheffield, a Labour member of the House of Lords, and Contributing Editor at Left Foot Forward.

There is a gender and ethnic segregation of occupations. Black, Asian and ethnic minority groups are more likely to be in lower paid jobs than their white counterparts.

Ethic minorities often lack trade union representation

Individuals from ethnic minorities are over-represented in social care, hospitality, cleaning, security, and other services and often lack trade union representation. Low wages condemn workers and their families to poverty; poor housing, education, healthcare, pensions and life chances.

Calls for mandatory ethnic pay gap reporting

In recent days, legislators from the UK House of Commons and the House of Lords have urged the government to introduce mandatory ethnic pay gap reporting in order to give visibility to discrimination and exclusionary practices.

Voluntary approaches have not had the desired result. Only 13 of the FTSE100 companies publicly report their ethnicity pay gap.

The President of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) told parliament that the ethnicity pay gap is over 25% in many companies. Inevitably, many are condemned to poverty, all because of the pigmentation of their skin.

Lord Boateng told the House of Lords that poverty rates are about 50% for Bangladeshi groups, 47% for Pakistani groups, 40% for black groups, 35% for Chinese groups and 25% for Indian groups, compared with 20% for white groups in the UK. There are also considerable gender differences.

Education is seen as a key to social mobility, but despite appropriate qualifications people from ethnic minorities find it difficult to reach the upper echelons of their workplace.

The 2020 Parker Review set a target for each FTSE100 Board to have at least one director of colour by 2021 and for each FTSE250 Board to have the same by 2024. The CBI President noted that “today 20 FTSE 100 companies do not have a single ethnic minority director and only 54 FTSE 250 companies have one ethnic minority director.”

Individuals of African origin face the biggest barriers

Individuals from African origins experience the biggest barriers. A report on boardroom diversity stated that here were no black chief executives, chief financial officers or chairs in any of the 100 biggest companies in Britain.

It is a similar story across the professions. Only 155 out of more than 23,000 university professors in the UK are black. Over the last five years, the number of university professors increased by nearly 3,000, but only 50 of these posts went to black individuals.

Last year it was reported that just six out of their more than 800 UK-based partners at the largest five law firms are black. Two had no black partners.

In 1987, the UK accountancy profession was the subject of a Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) probe into racism in the recruitment process. It published a document titled “Chartered Accountancy Training Contracts: Report of a Formal Investigation into Ethnic Minority Recruitment”. It documented conscious and unconscious racism in the recruitment process. The CRE promised to revisit the issues, but never did. Its successor bodies have not done so either.

Whilst somethings have changed, voluntary approaches have not brought the desirable rate of improvement. Ethnic minority staff at PricewaterhouseCoopers are reported to be paid 40.9% less than white colleagues. Ernst and Young had ethnicity pay gap of 48.9%.

Neither have the voluntary approaches resulted in diversity at partner level in big accounting firms. Last year, there were only 17 black partners in the eight biggest accounting firms despite increasing black, Asian and minority ethnic representation among staff. Only 11 of the 3,000 partners of the big four accounting firms were black. Deloitte had one black partner; Ernst & Young and KPMG had two each. PricewaterhouseCoopers had six.

Mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting is a ‘no brainer’

The CBI says that bridging the ethnicity pay gap could uplift UK GDP by up to £24bn a year. This would rejuvenate local economies. The Centre for Centre for Economics and Business Research says that gender, disability, ethnicity and other forms of discriminatory pay practices costs the UK economy £127bn in lost output every year. So surely, mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting is a no-brainer.

Since 2017, gender pay gap reporting has been mandatory for large businesses, i.e. businesses with over 250 employees. This can provide a template for ethnicity pay gap reporting. There is little cost of adopting such practices as most responsible businesses would already have the necessary information.

In addition, directors should be required to provide binding plans for reducing the pay gap and increasing diversity. Increased diversity and reduction of ethnicity pay gap must form part of executive remuneration contracts. The government itself can set the tone, for example by denying publicly funded contracts to organisations not reducing the ethnicity pay gap.

However, the UK government is opposed to mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting. It claims that the relevant data is difficult to collect data and would impose substantial costs on businesses even though the similar hurdles have been overcome for gender pay gap reporting. Meanwhile, millions of people are condemned to a life of discrimination and social exclusion.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers and to make the biggest impact we can in the next general election, we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 124 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.