No problem is solved unless we actually acknowledge the problem, if you acknowledge it you then have the duty to solve it.

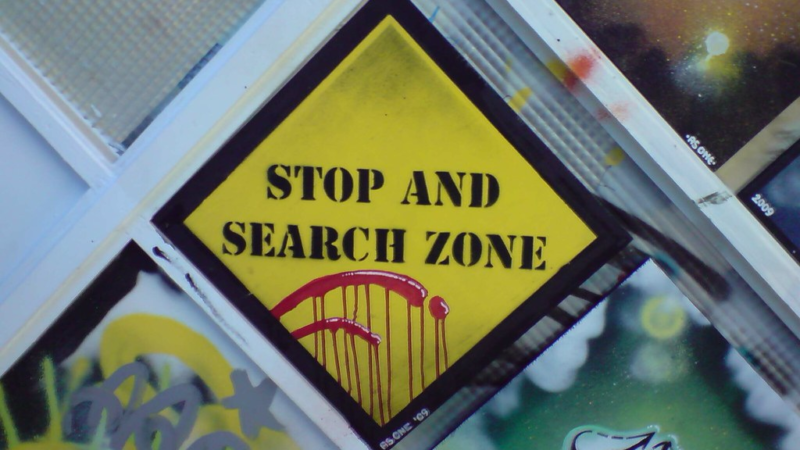

When it comes to knife crime, politicians and reporters continue to miss the point.

Knife crime has hit record levels with 44,771 offences in 2018-19 – with 49% of all knife crime offenders in London being teenagers and younger children.

Unfortunately, in attempting to tackle the root causes of this crisis, the Right leave out some crucial facts.

As of 2019, the number of police officers had declined by 13% since 2010-11. In the same period, knife crime increased by 46%. Linked to this, the Prime Minister recently pledged to increase the number of officers by 20,000 over three years.

What the official statistics will not tell you is that young people do not care about the police numbers at all. It is simply not on their minds – and it is quite bizarre to suggest that young people check if their local police stations have hired more officers before going out and stabbing someone.

Walking past 10 officers on the street as opposed to three officers will not avert young people from acts of violence. We have to look deeper than police cuts.

Fewer police officers will of course have an impact overall when it comes to public safety. But it will not change the mindset of the young people committing knife crime. It is the mindset of some young people that we should be seeking to revolutionise.

I can speak about my own personal experiences growing up in Newham – the poorest borough in London, where 52% of children are judged to be living in poverty. The fact is that a lot of our young people are walking around entrenched with trauma: trauma related to their economic, environmental and social circumstances. Ironically, over-policing is actually contributing to this trauma.

Among 16 to 24 year olds, unemployment rates are highest for people from a Black background (26%) compared to white people (11%).

Then there’s the mental health aspects of this crisis. Last year, Nazir Afzal, a former Chief Prosecutor of North West England, said that mental health issues “play a significant part” in the rise of knife crime. Mr Afzal, whose nephew died after being stabbed earlier last year, said that the services to tackle mental health problems are simply no longer there, TalkRadio reported.

When support does come, it’s often too late. When it comes to the racialised aspects of knife crime, black and minority ethnic people are 40% more likely than white Britons to come into contact with mental health services through the criminal justice system, rather than through referral from GPs or talking therapies.

Evidence also shows that people from black and minority ethnic communities are less likely to seek help at an early stage of illness, down to a combination of ‘lack of knowledge, stigma, inappropriate models of diagnosis and poor experience of mental health services’, according to the Race Equality Foundation.

On one side, trauma can trigger creativity – music, art and sports. But these are no replacements for the therapeutic and mental health support many young people unknowingly need. It is a constant sprint from depression. If you slow down it might catch you, if you run too fast, you will run out of breath and get caught anyway.

Those prone to crime are also often on the run from depression and anxiety, or from traumatic home lives. The ‘choices’ available to young people are often grim.

It is easy to dismiss the issue of knife crime by simply calling for an increase in police officers. But changing the mindsets of young people is a harder ask.

No problem can be solved until we actually acknowledge the problem. And if you acknowledge it, you then have the duty to solve it. Let us choose the harder right path as opposed to the easier wrong one. This is a matter that goes beyond politics. It’s about our humanity.

Jonathan Odur is a student at the University of Kent and also a freelance blogger, follow him on Instagram @after.decadence

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.