New Zealand's trust in government is twice as high as in the UK

I can thank the government minister Lord True for drawing my attention to the correspondence between two statistics.

I was pointing him to a telling survey showing that fewer than half of the public now consider the government “relatively trustworthy” or better.

He dismissed the YouGov survey as just “my view”, but then highlighted that it was only a few months since the last general election.

This left me reflecting on how the public trust pretty well mirrors the public vote: 44% of people voted Tory, and we thus got a government with the backing of the minority of voters. If you quote that as a percentage of registered voters it comes down to around 30%, even lower when you consider how many eligible voters are not registered.

The voting system is not the only aspect of our political structures that I’ve been highlighting this week. Another was political funding.

I haven’t yet found a place to use the metaphor “who pays the piper calls the tune”, but it has been very much at the forefront of my thinking.

My tongue was very firmly wedged in my cheek when I expressed concern about the hot water that Housing Secretary Robert Jenrick is cooking in over his approval of Richard Desmond’s Westferry development, I suggested that it would be in the interests of ministers for large private political donations to be banned.

Then they could have dinner with whoever they liked, and make decisions without fear of the taint of the “apparent bias” that a judge identified in over-ruling Mr Jenrick’s decision, which saved Mr Desmond £40 million after a £12,000 donation to Conservative Party coffers.

Democracy – it really would be a good idea, but we’re nowhere near it in the UK, and based on government activity, it is not getting any closer. As with so many issues banked up somewhere in the depths of Whitehall, there’s no sign of the manifesto-promised Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission, progress on which the House of Lords was trying to uncover this week.

Now if you could go knocking on doors right now, I doubt too many people would explicitly say “constitutional reform” is what we need. The pressure of hunger and fear of hunger, of worry about unemployment, of fear for the future of small business would undoubtedly be at the top of conversations.

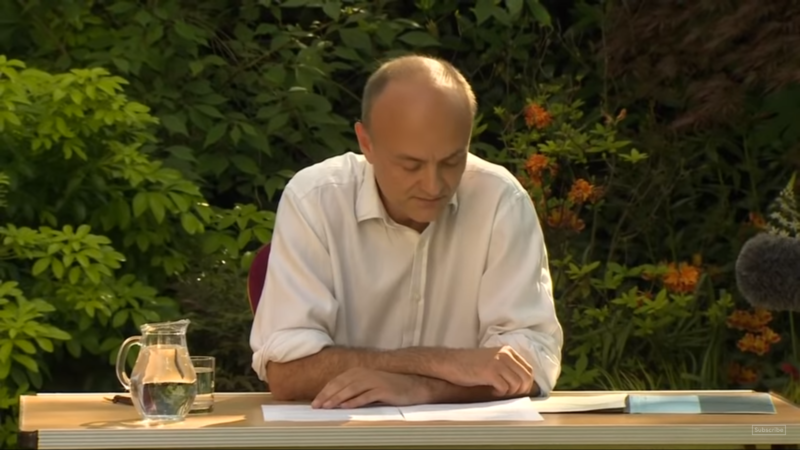

But underlying all of those is a powerful and dangerous distrust, and the desire for a functional, genuinely representative government would come through. Dominic Cummings’ Barnard Castle jaunt (after which preparedness to break the rules doubled) might now be top of comedians’ “go-to” list, but it is part of a much more serious problem.

People are not only confused about what the government is asking of them to keep the vital Reproduction rate of SARS-CoV-2 below 1, but they also don’t trust what the government is doing.

That shows in the YouGov poll, but it also shows in huge amounts of anecdotal evidence of people’s behaviour, from illicit haircuts to illegal raves.

And a young Manchester footballer is more in touch with public needs – and public views – than the much-vaunted PR machinery of No 10 Downing Street.

The Covid19 pandemic is a stern test for any government. The performance of any individual country is undoubtedly the product of many factors – one of them luck – but one thing is clear around the world, that the public’s trust in government is crucial to an effective response.

A comparative approach shows just how low the UK’s is, just as the height of the figures on excess deaths and Covid-19 positive test deaths show how we are “world-leading” in the worst possible way.

New Zealand has many practical geographical advantages, but it has also managed the lockdown well. With sad predictability, it had been declared clear of coronavirus, until two Britons arrived to bring it back to the Antipodean nation.

But Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern didn’t blame the UK for the breakdown. She didn’t bluster and boast about “worldleading systems”. She immediately publicly identified what went wrong, and changed the systems to make sure it didn’t happen again.

Eighty-eight percent of New Zealanders trust their government in its handling of the epidemic – about as high as you can imagine such a figure ever being. And so they follow the rules, and reap the rewards.

Covid-19 has exposed many obvious weaknesses in our systems – the impacts of austerity on government services, the impact of insecure, low-paid employment, and the disastrous overcrowding actively forced by government policies such as the bedroom tax.

But in the evitable public inquiry that will follow the shock of the virus’s arrival, the lack of democracy, the disastrous lack of public trust in and support for the government, will have to be put front and centre.

Constitutional reform – getting a modern, functional, democratic government in Westminster, but also one that ensures genuine devolution of power and resources to the local level – is essential in terms of improving the efficiency of government, as well as its legitimacy.

Natalie Bennett is an associate editor of Left Foot Forward and a Green member of the House of Lords

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers and to make the biggest impact we can in the next general election, we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 124 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.