Democrat and Labour selectorates seem to be choosing 'credibility' above purity.

The United Kingdom and the United States of America share a common heritage, common language, and many cultural ties and connections. Now they also share a common angst – the question of the future of their left-wing political parties.

Donald Trump’s surprising – even shocking – victory in the 2016 Presidential election brought a significant shift in public policy and economics in America. The Trump administration’s unabashed programme of right-wing nationalism is a stark contrast to the preceding eight years of Democratic rule under Barack Obama.

The Democratic Party was stunned by Hillary Clinton’s defeat, so much so that it was two years before they could even come to terms with it and consider what it meant for the future of their Party, and the politics of the left.

It is a similar debate now being faced by the Labour Party, following Jeremy Corbyn’s resounding defeat against Boris Johnson. Three months since the election, Corbyn is on his way out but the Labour party is still trying to come to terms with the scale and scope of the defeat, including some remarkable results in northern Labour strongholds which have shaken the Party to its roots. The idea that Blyth Valley would return a Tory MP would have been laughable not long before December. Tory winner Ian Levy’s margin of victory may have been small, but the swing to Conservative from Labour was massive.

Despite a divided Conservative Party arguing with itself over Europe, changes in Tory leadership, and a disastrous election campaign with Theresa May at the helm in 2017, Labour were simply unable to make their case to the British electorate, and suffered their worst General Election defeat since 1935. What price socialism now?

Candidates for the Labour leadership are busily trying to separate themselves across a spectrum of left-wing policies, hoping to avoid being tainted by Corbyn’s policies and leadership, whilst simultaneously at pains to show they are not Blair/Brown ersatz Tories. The televised Labour leadership debates have seemed to follow this trend.

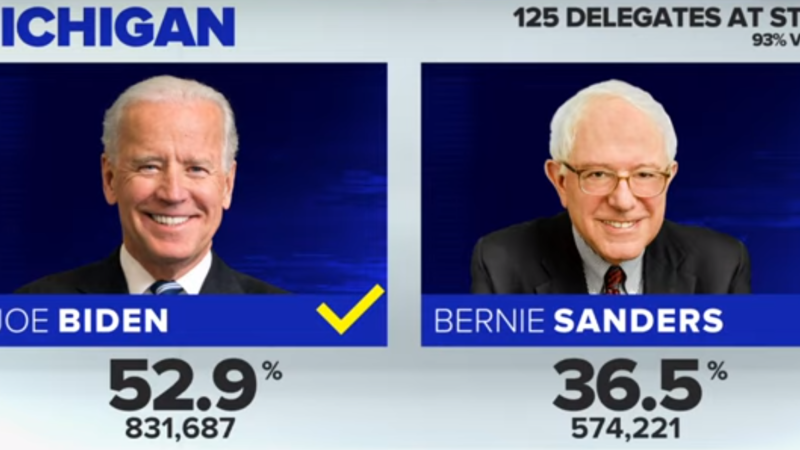

Should the Labour leadership candidates be concerned by the situation in the United States? Recent polling data indicates that the political landscape has shifted, and socialist messages may be hard to sell. Before Sanders’ routing on the second Super Tuesday this Monday, the writing may have been on the wall.

A recent Gallup poll tested what the American electorate think of particular candidate characteristics. The label of ‘socialism’ polled as the least attractive of all attributes, significantly below age, colour, gender, sexual orientation, and even religious beliefs. In a deeply religious country, Americans would rather vote for an atheist than a socialist.

This may be the fundamental reason why Bernie Sanders – certainly the most openly socialist candidate in a cluttered field for the Democratic nomination to run against Donald Trump in November – appears to be destined to be the bridesmaid rather than the bride once again. The RealClearPolitics website shows that while Sanders could beat Trump, Joe Biden’s margin would be larger.

What does this mean for Starmer and the Labour party? Starmer is a more ‘credible’ leader than Corbyn, just as Biden now seems more credible than Sanders. In the lead up to the General Election in December, Boris Johnson had a much better ‘net approval’ rating with the British electorate than his opponent – Corbyn’s net approval was -50% according to the YouGov poll, compared to Johnson’s -11%, a staggering differential. The British public simply did not see Jeremy Corbyn as a credible Prime Minister.

A post-election survey for LabourList identified the top criterion for those voting for the next Labour leader as ‘credibility as Prime Minister’. That was ranked more than three times as important (based on percentage of the respondents and their choices) than the next most important criterion: ‘maintaining the current Labour platform’. It seems getting into power is more important to the Labour party than the policies they would be elected on.

Labour might be hoping that whoever becomes the Democratic nominee ends up in the White House – and watching what that means for the chances of electing a Labour Prime Minister in Downing Street.

Professor John MacIntyre has worked in higher education for 30 years. He is a keen follower of politics on both sides of the Atlantic and lives in Northumberland.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.