Public health funding has been cut by £1 billion since 2014.

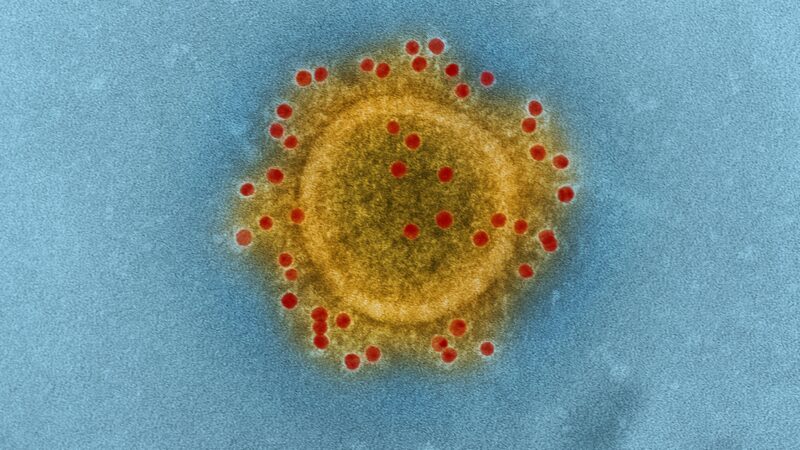

We have never experienced a peacetime crisis like coronavirus. The risk it carries, particularly to the most vulnerable, means an unprecedented change to how we work, live and use public services.

Global data is quickly allowing us to identify the most vulnerable. Chief amongst them are those with underlying health conditions like Type 2 diabetes, heart or respiratory disease, and cancer – conditions that are closely linked to alcohol and tobacco use, unhealthy diets and obesity. Tobacco use is likely to put people at heightened risk, independent of underlying illness.

Unfortunately, the public services aimed at helping people make healthy choices and reducing the incidence of these conditions – like stop smoking services; drug and alcohol addiction centres; and obesity interventions – have seen significant cuts over the last decade

Last year, the budget for public awareness campaigns on smoking cessation was slashed by a quarter. IPPR analysis shows that £850 million has been cut from local public health budgets in just the last five years. The poorest places have been hit first and worst – shouldering £1 in every £7 cut.

In short, the services that provide people the support they need to live healthy, happy lives – and to remain resilient to ‘health shocks’ like coronavirus – have been cut hard and repeatedly during the austerity decade.

This means worse health, reduced resilience, and missed opportunities to ease pressure on our strained NHS.

Transfering the blame

In 2013/14, public health functions previously overseen by the NHS were transferred to local government. The coalition government had proposed this as part of a ‘new era for public health’, with local government seen as better able to deliver wellbeing within the communities.

However, this decision was also combined with an approach to austerity that hit local government hardest – as a more politically convenient target than the health service. Government has subsequently squeezed public health budgets – either by reducing funding, or more usually by increasing the services it expects to be delivered without providing extra resource.

The approach has been cheered on and justified by a libertarian right, growing in confidence and stature. Nothing irks this grouping of politicians, think tanks and outriders more than ‘nanny state’ public health interventions. They contend that our health is solely a matter of personal responsibility. If we smoke, eat big portions or drink too much – as almost all of us do – then that’s our prerogative: as long as we live with the consequences.

Covid-19 exposes the critical failings of public health austerity.

No one is an island

First, as the research shows with increasing clarity, our health decisions are not made in a vacuum. They are shaped by social and environmental factors. That is, by the places we live; our employment; our financial situation; and the life chances open to us. A failure to invest in public health services and interventions is a failure to look out for the most vulnerable people in our country. It is entirely unfair they are left at such great risk when health crises then hit.

Second, it is incredibly short sighted. Margaret Thatcher was wrong: there is such a thing as society. There is no-one who goes through life without needing a little help – education when we’re young; childcare if we have children; a state pension when we retire; the NHS for when we’re ill. Not providing strong public health services just means the health service is left to pick up the pieces. And that reduces its capacity when, like now, it really needs it.

But the lesson hasn’t been learnt.

Buried announcement

Yesterday morning, government quietly released the new local public health budgets for 2020/21. The settlement is cleverly crafted. It provides just enough extra to look like a generous increase. But make no mistake, it consciously crystallises the cuts made during austerity. A small rise of around £150 million (not accounting for inflation) is pitiful compared almost £1 billion cut since 2014 and will leave us playing catch-up for a decade to come.

This all comes just two weeks before the new financial year begins. Many local leaders have faced significant uncertainty and have had to roll back plans as a result. They now turn to the task of planning a year of service delivery during a public health emergency. Data has still not been released to confirm whether this ‘rise’ is actually extra money – or just funding for new demands on the budget. There is a very real chance it will still constitute yet another cut for many important services.

This pandemic must be the moment government abandon their short-sighted resistance to public health programmes. They must resist cries of ‘nanny state’ and take a more empathetic approach. This means radically upgrading investment in the interventions and infrastructure that keep people healthy. It means actively steering that investment to the places and people who need it most. And it means delivering it, urgently, through a multi-year settlement at the Comprehensive Spending Review.

Health shocks like coronavirus are unpredictable and a continuous risk. Pandemics will come again and, not least because of anti-microbial resistance, could be even more severe. Demanding good public health is about being prepared for when the next crisis comes.

Chris Thomas is an IPPR Research Fellow.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.