Accounting expert Prem Sikka warns of a new social divide.

Perhaps contrary to popular belief, cash remains king for most Britons. 97% of population carries notes and coins in its wallets and 80% of people pay taxi drivers, newspaper sellers, window cleaners and gardeners with cash. But there is a growing trend towards a cashless society.

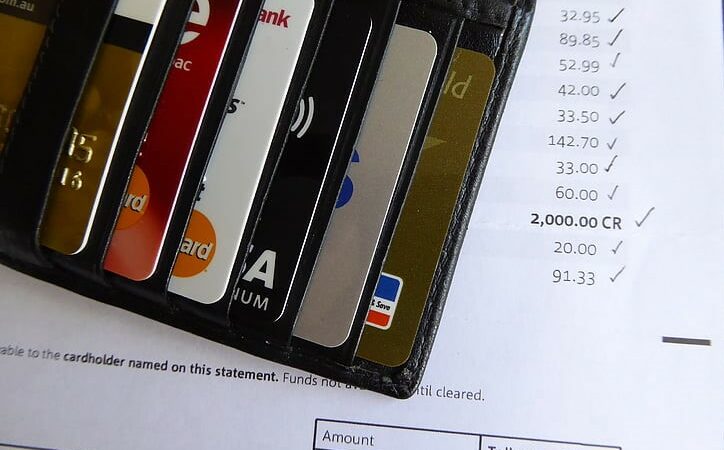

In brick-and-mortar shops alongside cash people swipe debit/credit cards, digital wallets and mobile phones for their purchases. This has been taken to the next stage with the emergence of shops which accept electronic payments only.

This week, Tesco opened its first cashless store on Central London and joins a number of bars, cafes and restaurants who do not accept cash. This trend is likely to accelerate as corporations chase higher profits by using technology and employing fewer humans. Cashless shopping poses big societal challenges though – about the power of corporations, the role of the state and inequalities in society.

The cashless revolution can speed up purchases, while traders say that it reduces the inconvenience of the daily banking of cash, risk of theft and the cost of business insurance. Of course, electronic transactions are not perfectly safe. WiFi connections, computers and databases can be hacked. Cards and mobile phones can fall into wrong hands and even be suspended, leaving customers and traders with no purchasing power. Storms, floods and power outages can take down the whole systems, leading to economic hardship and chaos.

The move to a cashless society, not only would change the economic but also the political power in societies. Banks, credit card and digital platform companies will effectively control the entire money supply. Yet they are not accountable to the people in any way whatsoever – while the role of elected governments in managing the economy would be constrained.

A cashless society requires everyone to have a bank account, debit/credit card, subscription to some payment platform or equivalent, and these are not always free. Some 1.23 million Brits do not have a bank account. Another report estimates that over eight million UK adults, and their dependents, would struggle in a cashless society. The elderly, infirm, poor, young, the unemployed, and people with difficult credit histories would not easily be able to secure access to electronic payments systems.

Migrants, refugees, temporary workers and homeless people won’t be welcomed by banks and given debit/credit cards. Some individuals with physical and mental health issues would find a cashless society difficult. A fully cashless society risks a form of economic apartheid – with a class of people shut off from the legal tender.

Electronic payments are very profitable for global corporations like Mastercard, Visa, American Express and PayPal. They get a percentage of every transaction, which may wipe out some or all of the economic gains associated with cashless transactions. Traders may indirectly pass some/all of the costs to customers in the form of higher prices.

The cost of transactions may be reduced by competition and new entrants, but the current incumbents aren’t easily going to let new entrants dilute their control. Last year, the European Commission fined Mastercard €570m (£503m) for anti-competitive practices which prevented retailers using cheaper banking services outside their home country.

In a cashless society, the privacy space would be severely eroded. What privacy for those sharing accounts – including those trapped in abusive relationships – if every transaction is visible to a partner?

A cash transaction is anonymous: it occurs between a customer and a trader who does not need to know the identity or the habits of a consumer. In a cashless society, all transactions are routed through a middleman – a bank or a credit/debit card company, who will log every single purchase, and sell data en masse.

The debt/credit card is the ID card of our time, and forms the basis of a surveillance society. We have little or no control over the data held by corporations and how they use it.

At times of crisis, people may like to hold cash. In a fully cashless society, that possibility would not exist. In the event of a possible banking crash, people would not be able to grab their cash or hoard it outside the banking system to manage the risks.

We may be some way away from a cashless society, but alarm bells should be ringing and societal responses are needed. These are issues we need to think about now, not later.

Many consumers prefer to transact in cash, especially for smaller value items. Such tendencies possibly persuaded Sainsbury’s to abandon its experiment with cashless stores. To prevent social exclusions, San Francisco, New York City, Philadelphia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts have banned cashless retail trading in brick-and-mortar shops.

The UK regulators need to follow suit and ensure that cash is accepted by all brick-and-mortar retailers and utilities.

Prem Sikka is Professor of Accounting at University of Sheffield and Emeritus Professor of Accounting at University of Essex. He is a Contributing Editor to LFF and tweets here.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.

One Response to “Prem Sikka: Why we should resist the rush to a cashless society”

Counting On Currency's Cash Per Diem - February 2020 Links | Counting On Currency

[…] Why we should resist the rush to a cashless society […]