The Spice Girls make headlines but sweatshop t-shirts are sadly the norm

News that nearly 5,000 garment workers in Bangladesh have been sacked for striking against low pay has received less coverage than did a related story ten days ago, and the disparity is worth exploring.

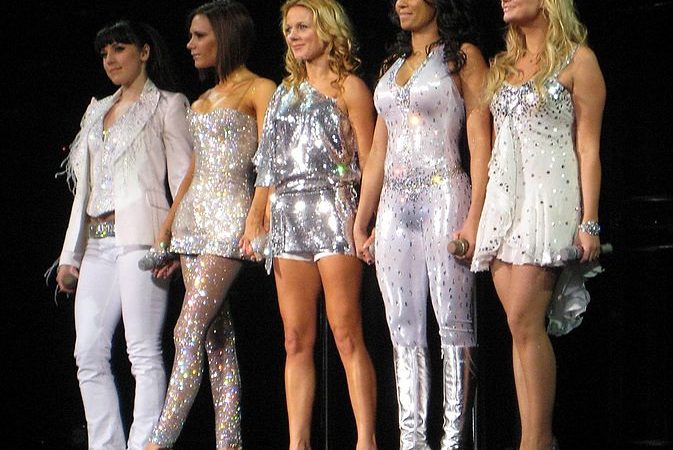

The earlier story, broken by the Guardian, revealed that Spice Girls “gender justice” T-shirts had been made in a factory in Bangladesh where female workers experience inhuman conditions – including pay of 35p an hour, forced overtime and verbal abuse.

The “scandal” comes from the easy charge of hypocrisy, however accidental, on the part of Comic Relief and the Spice Girls.

Yet without this embarrassing connection, these pitiful conditions would probably not have made the headlines, simply because these practices are so common place in far-away factories where the clothes we buy are made.

After working on these issues for many years, and having visited Bangladesh in September, I was not surprised that the Guardian investigation also uncovered that several of our favourite high street brands including Tesco, Marks & Spencer and Mothercare source from the offending factory, Interstoff Apparels. Unfortunately, the conditions reported are common in Bangladesh.

However, what struck me most about the reports was how routine the allegations were.

8,800 Tk (£82) per month is more than Bangladesh’s minimum wage for garment workers, which was recently increased to 8,000 Tk (£74).

But this wage is nowhere near what experts believe is necessary for a living wage, which would be 16,000 Tk (£148).

And while many brands have a policy commitment to moving in this direction, no high-profile high street brand is currently paying the workers in their supply chains a living wage.

The brands found to be sourcing clothes from Interstoff Apparels say they take these allegations seriously and are launching investigations or reviews, which is welcome.

But action to stem exploitation will be futile unless brands also look at how their business model and purchasing practices are create the conditions where exploitation occurs. This means the price they are paying suppliers for clothes and the unrealistic turn around demands they make.

Tesco, Marks & Spencer and Mothercare are the brands named in this case, but labour abuse is an industry wide issue. Our work at Business & Human Rights Centre taking up hundreds of allegations with brands over the last 14 years finds that all high street brands have this kind of exploitation in their supply chains.

Brands realise that consumers and investors expect them to take action to stop abuse. They talk extensively about their auditing of factories, which has turned into an industry of its own. But auditing has not seen any fundamental improvement in the lives of the women making our clothes.

The Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh had been audited numerous times before it collapsed in 2013, killing 1,100 workers. At its worst end, the auditing system has given brands plausible deniability when abusive conditions are discovered.

There clearly are some unscrupulous factory owners, and in many countries such as Bangladesh there are vested interests with the ruling class deeply intertwined with the apparel sector.

This should not obscure the fact that pressure from big brands on factories to continually cut prices puts pressure on factory managers.

This leads to abusive conditions like those in recent reports, with workers made to work excessive overtime and subjected to gendered verbal abuse.

The simple fact is that the price brands are paying for clothes is not enough for suppliers to pay a living wage. Factories in turn are only able to make a profit by squeezing the weakest actor in the value chain: the worker.

Some progressive brands acknowledge in private that the auditing system is not fit for purpose and that industry-wide action is necessary to tackle bad purchasing practices.

What is needed is strong collective action by brands to ensure prices allow for workers to be paid a living wage. Until this is addressed in every country where clothes are made for big-name brands, exploitation will continue, with women like those striking in Bangladesh most vulnerable to abuse.

Danielle McMullan is a Senior Researcher on Labour Rights at Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.