A new Home Office report shows the Tories' drug strategy is failing on its own terms.

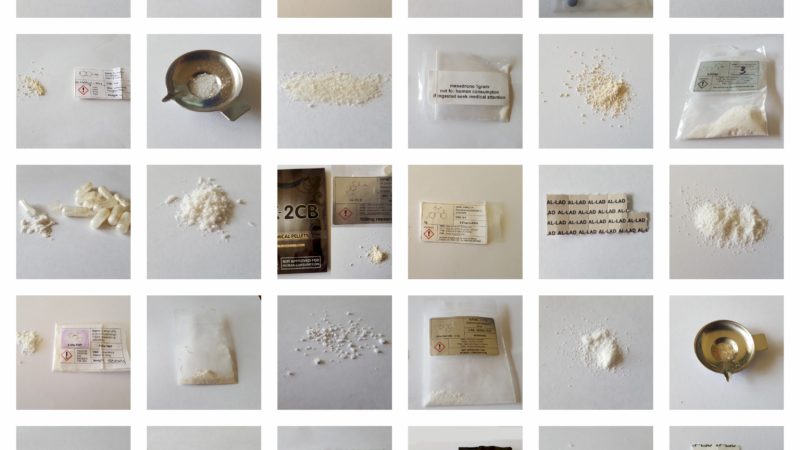

This week the Home Office released its review of its 2016 Psychoactive Substances Act (PSA) which introduced a blanket ban on the production, distribution, sale and supply of most psychoactive substances including former ‘legal highs’.

In 2015, Policing Minister Mike Penning said:

“The landmark Psychoactive Substances Bill will fundamentally change the way we tackle new psychoactive substances – and put an end to the game of cat and mouse in which new drugs appear on the market more quickly than government can identify and ban them.”

And after the Bill became an Act, Karen Brady Minister for Preventing Abuse and Exploitation claimed:

“This landmark Psychoactive Substances Act will fundamentally change the way we tackle these drugs and put an end to unscrupulous suppliers profiting from their trade.”

Has it done that? Not if the government’s own review is to be believed. True, the headline conclusion of the review tells a seemingly positive story:

“In conclusion, most of the main aims of the PSA appear to have been achieved, with the open sale of NPS [Novel Psychoactive Substances – so-called ‘legal highs’] largely eliminated, a significant fall in NPS use in the general population, and a reduction in health-related harms which is likely to have been achieved through reduced usage.”

But that’s not what the body of the report says… Let’s look at the goals of the Act one by one.

1. To put an end to the open sale of ‘Novel Psychoactive Substances’ (NPS)

“…open sales of NPS in shops and on clearnet websites have been largely eliminated. However, the evidence suggests that the main source of supply for NPS is now likely to be street dealers, particularly for synthetic cannabinoids.”

2. To put an end to the game of ‘cat and mouse’, where new substances appear on the market in response to legislation

“This does not appear to have been achieved…novel drugs which are not controlled under the MDA have continued to emerge since the introduction of the PSA.”

3. To reduce the number of people using NPS

“This appears to have been achieved for the general adult population…the exceptions to this finding are for the use of nitrous oxide among adults and the use of NPS among children, both of which have not changed… The evidence on NPS use among vulnerable users, including the homeless, is mixed, and where use has decreased there appears to have been some displacement from synthetic cannabinoids to ‘traditional’ controlled drugs.

In prisons, the PSA does not appear to have restricted the prevalence of NPS, with use of synthetic cannabinoids in particular appearing to have increased since the Act was introduced.”

“There is insufficient evidence to quantify the extent to which NPS users have substituted to other drugs, so it is not possible to identify whether the Act has led to an overall reduction in drug use.”

4. To reduce the various health and social harms associated with NPS

“This appears to have been achieved in the main, although… while there has been a reduction in NPS-related deaths across England and Wales, there has been a considerable increase in Scotland since the Act has been introduced”

So the review admits the PSA has failed to meet many of its goals – as predicted by experts:

-

While high street ‘Head Shop’ sales have stopped, the trade has just shifted to street dealers

-

The ‘cat and mouse’ game of new drugs coming onto the market as others are banned has continued

-

Use among children and the homeless have not fallen, and the review cannot say if overall drug use has fallen because even where adult use has reduced, people may have shifted to other banned substances instead

-

In prisons, use of synthetic cannabinoids (‘Spice’) in particular has increased while deaths directly attributable to NPS appear to have fallen in England and Wales, they have risen in Scotland

-

The review cannot tell if overall social and health harms have fallen because people may have just moved to other drugs – where deaths, for example from cocaine and MDMA use, have been rising sharply

The blanket ban on so-called ‘legal highs’ was supposed to cure the problem – including the substance Spice. But as experts warned before the new law was implemented, beyond the cosmetic success of ending legal sales in head shops, little positive has been achieved.

In many respects the situation has deteriorated. Trade in these drugs has moved from legal shops to criminal street markets, with problematic use a growing problem in UK city centres and prisons. At the same time Class A drug use and deaths have risen, suggesting drug use has just shifted not reduced, so the review can’t say if health and social harms have fallen.

‘Legal highs’ only emerged to replace prohibited drugs like cannabis, and ecstasy. Yet more prohibition was never going to be the answer.

Let’s hope this entirely predictable failure of drug war thinking prompts an extensive review of UK drug laws, including options for responsible legal regulation of drugs.

Martin Powell is Head of Campaigns and Communications at the Transform Drug Policy Foundation.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers and to make the biggest impact we can in the next general election, we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 124 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.