Why are we pumping billions into debt when there's another way to finance public investment?

There was plenty in this week’s Budget to be disappointed about. Namely the failed promise to end austerity, as well as tax cuts which will disproportionately benefit the wealthy. But there were also more big giveaways to the financial sector and the asset-rich which have often been overlooked.

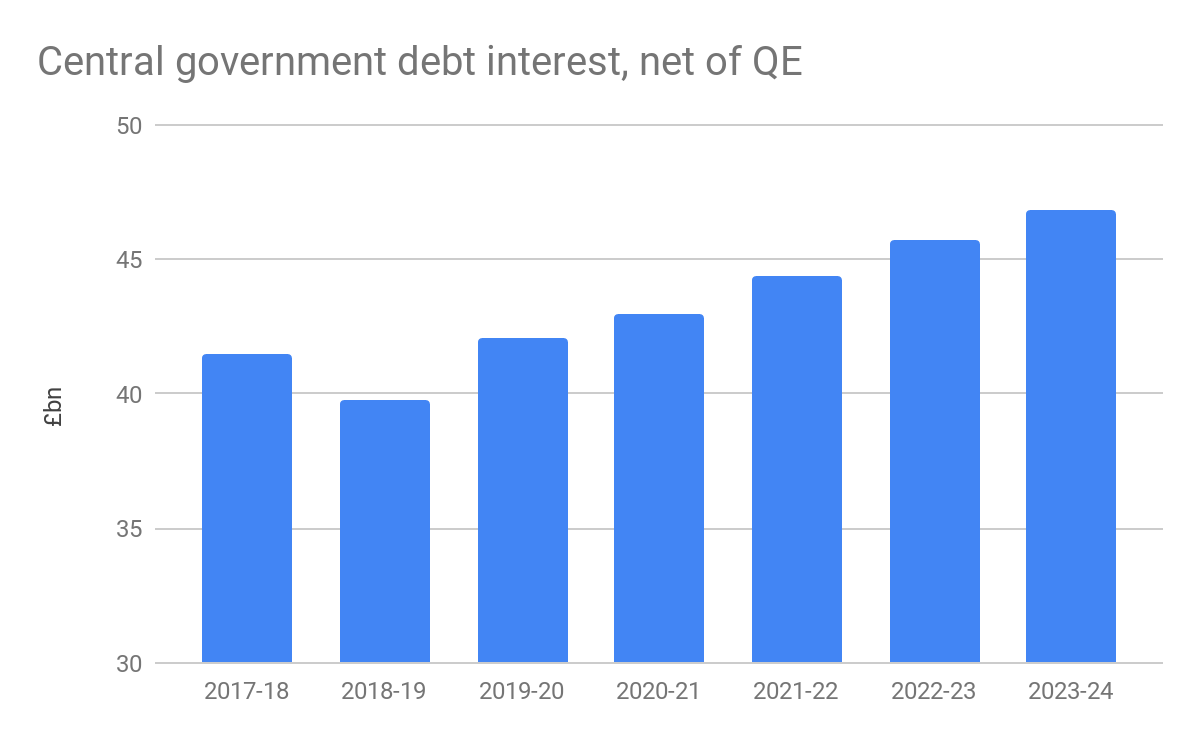

Philip Hammond was right to decry “the nightmare of wasting over £50bn a year on interest” on the public debt, as he introduced this year’s Budget.

But as the OBR’s analysis reveals, the amount of public money wasted on interest payments is actually set to rise every year as a result of this this Budget: from £39.8bn in 2018-19 to £46.8bn by 2023-24, after knocking off the amount the government ‘owes to itself’ through quantitative easing (QE).

Source: OBR

Such interest payments make up around 5% of total public spending, and more than is spent on most government departments.

In comparison, though we face a housing and climate crisis, the total budget for housing and the environment will only be £32bn in 2019-20. Worryingly, the amount spent on debt interest may grow even higher as global bond yields continue to rise.

Who do we owe?

Though some dismiss this as ‘debt we owe to ourselves’, such a characterisation is misleading. Like most financial assets, the vast majority of effective government debt is held in the financial sector and by those at the top of the wealth pyramid.

Pension funds indeed hold a sizable chunk of government debt, but the distribution of pension wealth is also less equitable than many assume, with nearly half of private pension wealth being held by the top 10% of households.

Therefore it might be better to think of government debt not as debt we owe to ourselves, but debt owed by the bottom 90% to the top 10%. In this way billions more spent on interest payments are billions extracted from the real economy by the financial sector and the asset-wealthy.

Without changes to a regressive tax policy in which poorer households are paying more as a proportion of their income, government spending on interest payments can be seen as another way in which ordinary households are subsidising the gains of the wealthy.

This is by no means to argue against increased public spending. Far from it. The issue is with how that spending is financed.

Funding change

Rather than paying for the deficit by borrowing from private lenders at interest, it is possible to cut out the middleman by using the central bank to fund deficit spending, through what is can be described as ‘overt monetary financing’ (OMF).

Just as the Bank of England has created £445bn to buy bonds and other financial assets from private holders through QE, we could have a form of ‘QE for People’, where the Bank creates money to buy bonds directly off the government, thus allowing increased public spending without increased flows of interest payments to private rentiers.

Such an approach to government financing would obviously require constraints against politicians ‘overheating’ the economy with deficit spending, such as full employment or (less hawkish) inflation targets, as well as policy interventions which deter bondholders from getting a free lunch from property or elsewhere instead. But ultimately such radical reforms may be necessary to create a fairer basis for government fiscal policy.

RBS swindle continues

The Budget also saw the government quietly set out a new plan for selling off the remainder of its shares in RBS by 2024.

Buried in the OBR report are increased estimates of the amount the British public are set to lose from the sell-off, from £26.9bn to £28.5bn. This is because in 2008 the government spent £45bn bailing out RBS at 502p a share, but the bank’s share price has since collapsed, currently standing at less than half that value.

However this year RBS reported its first profit since the financial crisis, and in October it paid out its first dividend. The OBR therefore points out that the government will be losing £2bn in dividends with its share sell-off plans.

Shedding an asset like RBS as soon as it becomes profitable would be another case of risks being socialised and rewards being privatised. It is also expected that RBS’ share price will increase as the government sells more shares, offering another windfall to wealthy pockets.

Not only will continuing the RBS privatisation see the government transferring more income to private shareholders, but in doing so it would also surrender the opportunity to put the bank to work in the public interest.

Britain’s economy has long been the victim of a vampiric financial sector extracting value for wealthy rentiers, to the cost of an estimated £4.5tn from 1995 to 2015. This Halloween Budget has only made things worse.

Simon Youel is Policy and Media Officer at Positive Money.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.