Wonga is just one symptom of a broken economic model.

Wonga may be dead, but exploitative lending, as well as the conditions fuelling it, remain very much alive.

Wonga is just one symptom of a broken economic model. After a decade of stagnant wage growth, 1.4 million families in Britain resorted to short-term and high-cost credit in order to pay for everyday household costs in 2017.

High cost creditors like Wonga represent a huge drain on the economy, with 1 in 4 of Britain’s poorest households spending more than a quarter of their monthly income on debt repayments. This means that around £21bn a year is simply being siphoned into the pockets of lenders like Wonga, who produce little of value, in interest payments, instead of being spent on goods and services in the real economy.

When the FCA stepped in to regulate Wonga’s unscrupulous lending activities in 2014 it became clear that the company’s business model could no longer function. This was reflected across the industry, with the number of payday loan companies falling from over 400 in April 2014 to just 144 by the end of 2016. But while regulation might have killed off the likes of Wonga, the cost of living crisis has simply been exploited by other high-cost creditors, such as credit card lenders, who, unlike payday lenders, are not restricted by a 100% cap on debt costs.

Growth in credit card lending has more than doubled since 2014, while growth in other forms of consumer borrowing begins to slow. The Bank of England’s money and credit data for July 2018, released on Thursday, shows borrowing on credit cards increasing by 8.9% annually, while growth in other loans and advances lags behind at (a still worryingly high) 8.2%.

Four in ten British adults struggle to make it to payday, of which nearly a third do so because of credit card repayments.

The case of Wonga also provides an important lesson about the darker side of the so called ‘fintech’ (financial technology) craze.

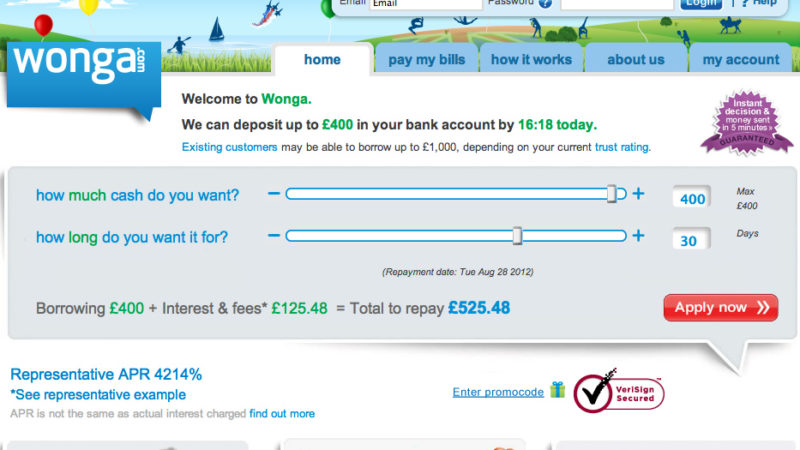

Instead of the liberatory potential of technology being used to to improve people’s lives, companies like Wonga have used it to maximise the efficiency at which they prey on vulnerable customers. Wonga was initially lauded as London’s first major fintech company, using software to automate the personal lending process. But this use of fintech without ethical safeguards meant irresponsible lending prospered. Now Wonga’s lucrative source of profits – lending money at high-interest (5853% APR) to people who couldn’t afford to pay it back – has come back to bite.

As well as taking action on high-cost credit in general, more scrutiny therefore needs to be applied towards those like Wonga who’ve ridden off the tech bubble, to ensure they aren’t sugar-coating exploitative business models under the guise of ‘innovation’.

The FCA’s action against Wonga shows the impact regulation can have on curbing exploitative practices. But the systemic nature of the wider issue means more transformative options need to be considered, such as using QE to wipe off problem debt, and ending austerity so as to create sustainable demand without an unnecessary and damaging debt overhead. By shying away from using their powers to create money, policymakers are simply leaving a gap to be filled by parasitical and crooked schemes like Wonga.

Simon Youel works on media and policy at Positive Money. He tweets here.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 117 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.