Tomorrow, the latest inflation figures will be published. The reaction, if recent months are a guide, will be panic and alarm at the continuing high level of consumer prices, the impact on household budgets and the possibility of rising interest rates.

I want to question whether we are drawing the correct policy conclusions from the recent rise in inflation. I would argue that the focus on higher prices is misplaced and risks drawing attention from more important economic questions.

The government has set an inflation target of 2 percent. If the rate of CPI is more than one percentage point away from the target then the Governor of the Bank Of England must write open letter to the Chancellor explaining why the target has been missed and what action the Bank intends to take.

What to expect

If on Tuesday inflation is above 3% then Governor Carney will be sharpening his quill to write to Mr Hammond. This will be the first such letter since December 2016. That’s right it is only a matter of months since the Bank last missed the government’s target.

From May 2015 until last December the inflation index was more than one percentage point below target, at times touching 2 percentage points below target. While commentators were less alarmed by low inflation, for economists the reverse is true. Zero inflation is far more dangerous than inflation at 4%.

High inflation can always be addressed by raising interest rates. However, central banks have no ready answer to deflation – when prices are falling. Deflation combined with high levels of debt is a recipe for recession.

In the US economists have been pushing the Federal Reserve to raise its inflation target above 2 percent. Janet Yellen, America’s central banker, has acknowledged the importance of the issue.

So if 3% inflation is healthier than the levels we saw last summer, should we not still worry about living standards?

Wages

The true cause of declining real wages is the slow pace of wage rises pursued as a deliberate policy. Imposing a 1 percent pay cap is unjust precisely because it takes account neither of inflation nor of rising national income.

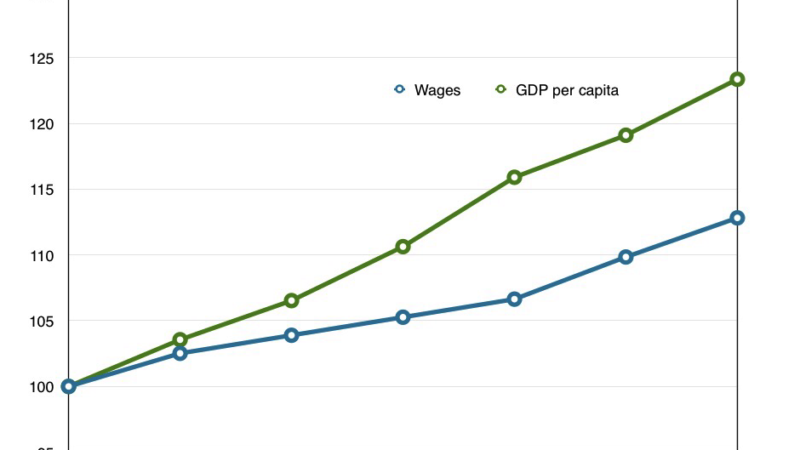

When the economy is growing we should expect wages to keep pace. In Figure 1 (above -sources Bank of England, ONS) I compare the level of the median wage to the level of GDP per head, with both scaled to 100 in 2010. It shows that the pay of the average worker has grown more slowly than the growth in national income per head. The average worker is not gaining the full fruits of her labour.

There are two possible explanations: firstly, the share of national income going to wages has fallen or, secondly, more of the wage share is going to workers earning above the average. So inequality is also part of the problem.

Interest rates

It is likely that inflation will begin to fall, if not this month then later this year. The rise in prices is mainly driven by rising import prices due to the fall in sterling after the referendum last June.

A one off rise in prices affects the inflation index for 12 months. So price rises last June drop out of the inflation figures this June. The rise in import prices isn’t passed on to consumers right away. Firms may sell existing stocks at the old price or may take a hit to profit margins. The effect of sterling’s fall takes time to reach the consumer price index but the index falls back at the same pace as it rose.

For this reason the Bank of England would be making a serious mistake if it chose to raise interest rates in response to the change in sterling. The index will fall back of its own accord.

Indeed it could be that rising import costs are masking an underlying problem of low inflation or deflation. When the sterling effect wears off we may find inflation once again dangerously low.

Conclusion

The analysis here is out of favour with most commentators.They prefer a narrative which blames Brexit for all economic ills, including falling real wages. The referendum triggered a fall in the value of sterling which caused inflation eroding household incomes.

This story ignores the fact that real wages were falling from 2010 to 2015 well before the referendum. Leaving the EU will not make us richer, but it should not blind us to the true economic challenges.

The underlying problems are low wages and the risk of deflation.The solution to both is higher pay. Britain still needs a pay rise.

Jos Gallacher is a member of the Economic Policy Commission of Labour’s National Policy Forum.

Left Foot Forward doesn't have the backing of big business or billionaires. We rely on the kind and generous support of ordinary people like you.

You can support hard-hitting journalism that holds the right to account, provides a forum for debate among progressives, and covers the stories the rest of the media ignore. Donate today.