From hyper-inflated egos to inevitable splits, the factors that stopped the SDP Liberal Alliance in its tracks in the 1980s will eventually destroy any new centre party.

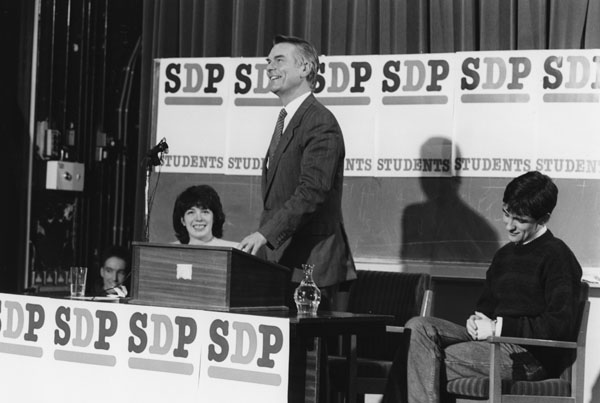

Pic: David Owen’s SDP was hammered by Britain’s voting system – and was eventually forced to merge with the Liberals.

Once more, the media buzzes with stories about a new centre party, made up of non-politicians, which may launch imminently. It has renewed rumours of a post-Brexit Labour split.

But beneath the froth on this cappuccino is the same bitter reality: the factors that stopped the SDP in its tracks in the 1980s will eventually destroy any new centre party.

I am a veteran of the SDP Liberal Alliance. I campaigned at the euphoric by-elections of Warrington, Croydon, Crosby and Hillhead. But I was also there for the fights over seat share-outs, the clash of egos at the top, and the temper tantrums, public and private, over policy.

In 1983 and 1987, I stood on the stage, my fake smile in place, as the returning officer read out the parliamentary election results. I came a respectable second both times, but no one cares who comes second.

With this experience in mind, I offer the following practical points.

Under the first-past-the-post voting system, a broadly popular centre party is likely to find support more or less evenly spread across the country. But you only win seats if you pile up votes in specific areas. Getting 30% everywhere does not guarantee a single parliamentary seat.

The Liberals polled six million votes (19% of the popular vote) in February 1974, emerging with only 14 seats, mostly in their historically strong areas of the Celtic fringe.

However, in 1997, 2001 and 2005 they targeted their resources narrowly and were rewarded with 46, 52 and 62 seats respectively on a 17%: 18% and 22% share of the vote. There’s a reason successive Tory and Labour governments have rejected proportional representation. And there’s a reason Denis Healey accused the SDP and the Alliance of splitting the anti-Tory vote, guaranteeing 18 years of Conservative rule.

If more than one new party emerges in the next year – the comfortably-funded United for Change, and a breakaway group of Labour MPs – they will cancel each other out if they don’t work together.

Those planting stories about United for Change claim somewhat implausibly it has £50 million. But money can’t necessarily buy you power. Ask Meg Whitman, who spent $144m of her own money trying unsuccessfully to beat Jerry Brown to become governor of California in 2011. In 2015, UKIP spent £2.9m and won a single parliamentary seat. At the same election the SNP spent half that sum and returned to Westminster with 56 seats.

The members of a new centre party may share an analysis of what is wrong with politics. However, finding consensus on the changes to make is more difficult.

The SDP quickly ran into its first parliamentary split when confronted by Norman Tebbit’s bill on the closed shop in February 1982. Divisions between the Liberals and SDP on defence policy thereafter diverted attention from all the issues on which they agreed.

Will mutinous Labour MPs or the United for Change project of businessman Simon Franks find agreement on constitutional reform, outsourcing, our role in the Middle East, Hinckley Point or HS2? Do they want a second referendum on Europe or a soft Brexit or for Parliament to have the final say?

It requires a certain personality to push yourself in front of a microphone, believing you know best and that the public wants to hear from you as often as possible. Someone who founds a new party, believing everyone else has got it wrong, will likely be ‘alpha’.

Now, imagine several alpha people, self-confident enough to break away from their political tribe. How well will these people play together? Judging from the clashes between David Owen, Roy Jenkins and David Steel during the Alliance, the answer is not too well. The businesspeople behind the other vehicle, United for Change, may have been successful at an early age: they may believe they are unique. That they can sort out British politics where others have failed.

But it’s like young novelists declaring they don’t need to read Austen or Dickens because their fresh genius is so exceptional: out with the old ways – they have nothing to teach me. A businessperson is often surrounded by yes people. It will come as a shock to someone who has never held elected office, even at parish council level, when they are criticised by the media and others who aren’t on their payroll. Simon Franks’ boosters say he is like Macron breaking the mould of French politics. But Macron had been in President Hollande’s cabinet. Canvassing may come as a shock to the system.

Given these factors, how likely is it they will come to a pact with each other or with the existing centre-left party, the Liberal Democrats? Well before the SDP launched in 1981, Roy Jenkins, the godfather of British political mould-breaking, was clear his new party must merge with the Liberals. His colleagues were not so certain.

There followed a long, painful process, nudging them toward a pre-electoral deal to ensure the SDP didn’t stand against Liberals, eventually leading to full merger in 1988. Seat allocation absorbed time and energy that should have been put into campaigning. It caused suspicion and clashes that never healed, in some cases. All for a disappointing 25.4% of the vote in 1983 – and 23 seats – and then 22.6% and 22 seats in 1987.

Boosters will say we are living through a new paradigm – that people are less deferential to traditional parties, and there is demographic change. In fact, politicians have been fretting about this since the industrial revolution.

If Jo Grimond or Roy Jenkins were alive, they might chuckle at the notion that this time the realignment of the left will be different. They might also wonder why all the characters involved don’t just take over the Liberal Democrats.

Becky Bryan was an Alliance Parliamentary candidate in 1983 & 1987.

To reach hundreds of thousands of new readers and to make the biggest impact we can in the next general election, we need to grow our donor base substantially.

That's why in 2024, we are seeking to generate 150 additional regular donors to support Left Foot Forward's work.

We still need another 124 people to donate to hit the target. You can help. Donate today.